True Detective Reinvented the Noir Tradition

Tuesday, August 11th, 2015 • Writing

Now that it’s complete, the second season of HBO’s True Detective can be properly judged, and, I think, elevated to its rightful status: a noble experiment at worst and, at best, an erudite and deeply-felt reaffirmation of the ninety-year-old Noir tradition that’s threaded through our literature, movies and myth. At the very least, Season 2 deserves to be assessed as a whole, given its novelistic structure and grandiose thematic and narrative ambitions—considered piecemeal, the individual parts have elicited scorn and derision that they tended to deserve. The early episodes, in particular, were disastrously weak; had they been book chapters, any competent editor would have demanded that they be rewritten. (Re-watching the premiere, I was astonished at its plodding, pretentious clumsiness, especially in comparison to the story’s thrilling, tragic final hours.) But now that we have all the pieces, the puzzle fits together into a surprisingly rich and satisfying picture—Nic Pizzolatto’s grim, intricate eight-part crime saga was an extraordinary overreach that, in the end, conquered a surprising and impressive amount of the vast territory it claimed.

Of course, from the beginning Season 2 suffered in comparison to its predecessor, which was a home run of Babe Ruth proportions—the chemistry between leads Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey and (in McConaughey’s case) the once-in-a-lifetime alchemy of a perfect match between actor and character elevated “Rust Cohle” to instant, iconic immortality. Season 1 had none of the hesitance and awkwardness of its successor—the unspooling of consecutive Louisiana murder investigations (expertly framed by an Internal Affairs probe a decade later) was so suspenseful from the moment it started, its dense philosophical cohesion so indelibly rich, that all subsequent disappointments (including what many considered a stunningly anticlimactic and unsatisfying denouement) were forgiven or overlooked.

The arrogant neo-Nietzschian figure Pizzolatto’s cut—his grandiose pronouncements and tendency to sneer at his critics—didn’t help: when Season 2 stumbled out of the gate, it was easy to cast him in the hubris/nemesis template of Michael Cimino or M. Night Shyamalan (both of whom followed up extraordinary debut successes with disastrous pratfalls like Cimino’s studio-sinking Heaven’s Gate). After the first episode of the new season, I was convinced (along with nearly everyone else) that we were witnessing just that sort of harder-they-fall comeuppance. But things changed—by the time the story had performed its unexpected 66-day time jump (after the show-stopping massacre that ended Episode 5) it was clear that the deep historical and artistic roots of this vast Los Angeles tale—and its ravenous need to devour every conceivable Noir archetype—were bearing strange, rich fruit: a modern-yet-ageless detective story that can stand alongside nearly any previous attempt to master the genre.

Noir is less about film than literature—it actually begins with Ernest Hemingway. After his WWI novels The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1927)—in which the moral chaos and vertigo of wartime are examined both on and off the battlefield—Hemingway explored the darkness of peacetime in To Have and Have Not (1937), a crime story built along a Marxist armature that (largely thanks to Howard Hawks’ 1944 Humphrey Bogart/Lauren Bacall movie) has been retroactively cast as the beginning of Noir. In “Hemingway and his Hard-Boiled Children” (1968), literary essayist Sheldon Norman Grebstein credits Hemingway with inventing a worldview in which

Crime is the specific social equivalent of war, and its prevalence signifies that no watchful deity and no meaningful pattern of order rules over man. The overwhelming impression derived by the reader of Hemingway is that of a violent world, a world at war, a world in which anarchy prevails. Hemingway’s depiction of violence, although it is in frequency by no means his major concern, is nevertheless perhaps the most vivid and memorable aspect of his art. And even where there is little or no violence, as in The Sun Also Rises, we are given the sense of breakdown, fragmentation, disintegration. In such a world, toughness seems the only means of survival […] Throughout Hemingway’s early work, and despite the keen social consciousness of most of it, law neither guides human conflict not seemingly has much relevance to it. No characters in modern fiction exercise greater moral awareness than Hemingway’s; none struggle harder for moral certainties; and almost none achieve such little success.

Hemingway’s stylistic successor was Dashiell Hammett, a former private detective who (along with Raymond Chandler, a decade later) debuted in The Black Mask, a pulp magazine launched by august literary critic H. L. Mencken (working with drama critic George Jean Nathan) in 1920 for the express purpose of making money with cheap crime stories in order to support Mencken’s more high-toned publications. The stripped-down style of Hammett and other “hard boiled” writers was not held in high regard: Herbert J. Muller (in his exhaustive 1937 study Modern Fiction) sneered that “this ‘cult of the simple’ appears in various forms in the modern world [including] the ‘hard-boiled school’ […] It is usually a sign of surface restlessness, a craving for novelty or thrill—the popularity among the sophisticated readers of novelists like Dashiell Hammett is more a fad then a portent.” But Muller allowed that “it also represents a serious effort by some intellectuals to find happiness in the mere being or doing of the great mass of common people.” And others acknowledged the importance of Hammett’s stylistic advances: Chandler wrote that Hammett had a style “but his audience didn’t know it, because it was in a language not supposed to be capable of such refinements” – Hammett was “spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

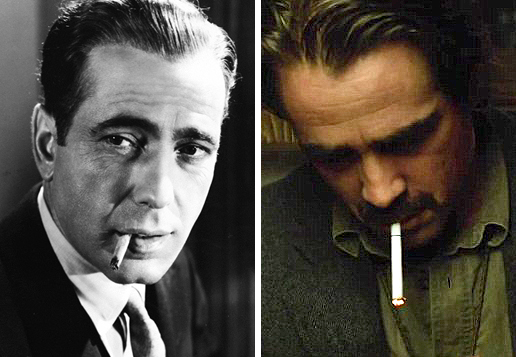

It took decades for Hammett’s crime stories to be accepted into the literary canon, since their clean, spare surfaces and tawdry subject matter disguised their artistry. As critic Phillip Durham wrote in “The Black Mask School” (1968), “The idea that style is the American language—discovered independently by several writers in the hard-boiled genre—is unquestionably one of the most significant aspects of the evolving, hard-boiled tradition. Style, then, is where you find it: not restricted to the drawing room or study, but equally discoverable in the alleys […] Hammett went to the American alleys and came out with an authentic expression of the people who live in and by violence.” Hammett’s best work—the landmark novels Red Harvest (1927), The Dain Curse (1928), The Maltese Falcon (1930), and, especially, The Glass Key (1931), operate like Hemingway’s crime saga in presenting a world with no natural moral order; a narrative environment in which boundaries between the light and the dark are hopelessly blurred and the detective and criminal are both cast adrift, groping for right and wrong. According to Hammett, The Maltese Falcon’s protean hero Sam Spade (best remembered via Bogart’s onscreen portrayal ten years later) “had no original…He is a dream man in the sense that he is what most of the detectives I worked with would like to have been: a hard and shifty fellow, able to take care of himself in any situation, able to get the best of anybody.”

Raymond Chandler is to Hammett as William Faulkner is to Hemingway: a baroque, romantic alternative to the ice-cold modernism of the early “hard-boiled” style (in fact, Faulkner himself wrote the script for Howard Hawks’ 1946 movie of Chandler’s 1939 novel The Big Sleep – and Bogart, again, embodied the central role; if Sam Spade was Bogart’s Indiana Jones, The Big Sleep’s sardonic Phillip Marlowe was his Han Solo). Chandler exchanged Hammett’s lonely Edward Hopper minimalism for a dizzying, lush complexity – and, more important, abandoned Hammett’s abstracted cityscapes (like the Hobbes-inspired “Personville” of Red Harvest) for the poisoned sprawl of Los Angeles, permanently affixing the Noir tradition to that city. As Herbert Ruhm argued, “Chandler is indisputably the best writer about Urban California […] [He] succeeds as no one else has succeeded in portraying Los Angeles, including Hollywood, and it seems at times that it is neither the violence nor the solution of the mystery Chandler is interested in as it is the city and the people.” “Mr. Chandler,” W. H. Auden wrote in 1962, “is interested in writing, not detective stories, but serious studies of a criminal milieu, the Great Wrong Place, and his powerful but extremely depressing books should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.”

Noir migrated from page to screen in the 1940s, where the simplified scenarios meshed perfectly with wartime frugality (the movies were famously underlit to save set-building costs), but the primal, nihilistic thrust of the original stories got blunted by Hollywood: John Huston’s earnest retelling of The Maltese Falcon (1941) distorted and cleansed the novel’s essential ruthlessness (and cast girl-next-door Mary Astor as the book’s terrifying femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy—a role that calls for an Angelina Jolie). Hammett would not get adequate cinematic treatment until decades later, when the Coen brothers smelted Red Harvest and The Glass Key into their stylistic breakthrough Miller’s Crossing (1990). (Red Harvest also inspired Kurosawa’s 1961 Yojimbo, which was itself remade first as the 1967 Sergio Leone/Clint Eastwood classic A Fistful of Dollars and again as Walter Hill’s 1996 Bruce Willis vehicle Last Man Standing.) The brutality and moral chaos of Noir – the Hemingway vision of a senseless world, viewed through the lens of California crime stories – had largely vanished from movie screens by the late 1960s, when Pauline Kael famously identified the “Urban Western” (starting with Dirty Harry and continuing through the Lethal Weapon series) as the new template for cop movies—a safe, Manichean world of vigilante heroes who “go rogue” in order to uphold and restore a moral order, like the Arthurian figures of Old West legend.

But despite superficial, essentially fraudulent camp pastiche like Body Heat (1981), Dead Again (1991) and The Usual Suspects (1995), the central Noir ideas have survived cinematically, through occasionally-successful recreations like the period-pieces Chinatown (1974) and L.A. Confidential (1997) and fringe experiments like William Friedkin’s slick, nightmarish To Live And Die in L.A. (1985), James Foley’s striking Jim Thompson adaptation After Dark, My Sweet (1990), or the stunning extensions of the L.A. Noir concept into science fiction (Ridley Scott’s visionary 1982 classic Blade Runner), surrealism (David Lynch’s astonishing triptych of 1997’s Lost Highway, 2001’s Mulholland Drive and 2006’s Inland Empire), Warholian Pop-art pastiche (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, 1988) and even computer games (Rockstar’s innovative 2011 L.A. Noire). Novelists like Walter Mosley, James Ellroy, Thomas Pynchon (whose 2009 postmodern Los Angeles neo-Noir shaggy-dog-tale Inherent Vice was just brilliantly translated into celluloid by Paul Thomas Anderson) and Cormac McCarthy (who skated completely off the deep end of reheated Noir philosophy with his debut screenplay for last year’s disastrous The Counselor) still can’t resist the lure of the Los Angeles crime story and all of its gaudy opportunities to meld the lowest human behaviors with the highest existential philosophy.

Drunk with hubris, Pizzolatto chose to take all of this on at once, and the result has been maddening, frustrating, impenetrable, inept, uneven, rushed (both in its execution and unmistakably in its conception and production) – but, finally, remarkable: as pure and unalloyed a resuscitation of the hybrid literary/cinematic Noir tradition as has ever been attempted. The dizzying, numbing complexity (Faulkner was asked to explain a mysterious dead body that appeared halfway through The Big Sleep and was never mentioned again; baffled, he contacted Chandler, who had forgotten the whole thing); the vast, cynical corruption of all public and private institutions; the endless booze and drugs and cigarettes; the dizzying, hallucinogenic sprawl of the city and its hapless, damned inhabitants; the moments of fragile and delicate sentiment and nobility that are mercilessly crushed and forgotten; all the decades-old elements of Noir are not just reconstructed but are blown up to epic, mythical proportions—Pizzolatto does to Los Angeles what Leone did to the Old West, expanding its scope and scale beyond any journalistic depiction of reality, so that the primal human elements of darkness and chaos, justice and sacrifice are cast in vivid, operatic relief. We have a parched city that needs water (as in Chinatown); a shortage of busses contrived to subsidize a rail system (like the freeway-based conspiracy in Roger Rabbit); contaminated land; lethal desert showdowns; prostitution rings; sabotaged investigations; and, finally, broken and maimed protagonists propelled past the limits of the public institutions that have failed them and their own faltering endurance, into an endgame where they must stand or fall based on nothing but whatever shreds of decency and grit they can muster. The modern touches—e-cigarettes; GPS transponders; Blackwater-style mercenary groups; Russian mobsters; TMZ exposés; sexual harassment charges (and the resulting “sensitivity training” requirements); ankle monitors; Viagra and MDMA; memories of the 1992 riots—not only don’t interfere with the eternal Noir elements but actually enhance their potency: the characters’ apprehension that they’re living out an unchangeable template—that they can’t escape the “world they deserve”—lends a fatalistic nuance to the story. (“Some of these sheds have been here since the 1930s,” the state attorney notes as the detectives finally find the remote murder scene.) When Bezzerides’ father tells Velcorro that he “must have lived a hundred lives,” he could be referring to the archetypes that stand behind his character, and the dozens of writers who have mapped out this dark territory—the story that “will never blow over”—down through the decades.

But, in the end, True Detective Season 2 was Pizzolatto’s own—and the circumstance of his empowerment as dictatorial auteur, as lone author, allowed the creation of a flawed but unique work, as far away from the focus-tested and homogenized Hollywood product of the day as could be imagined. Pizzolatto took on the authorless expanse of Los Angeles, and the countless attempts to impose identity onto its endless baked landscape—through lineage, through ownership, through crime, and, as in every Noir tale, through the struggle of the detective—and, mostly, succeeded in making his mark. Velcoro and his “hundred lives” are the repeated images of the same primal figure, Hammett’s “dream man,” a grizzled, timeless hero who transcends the specificity of any author or decade, whose hopeless struggle against the rotted fabric of this vast, haze-covered city is the same every time—he has a name, but, as Leonard Cohen whispers, never mind.