Saul Won’t Break Bad—And That’s Good

Monday, March 9th, 2015 • Writing

America’s dubious relationship with criminal defense, onscreen and off, has hit an interesting cultural speed bump with AMC’s new hit Better Call Saul, Vince Gilligan’s innovative prequel to—and, really, moral inversion of—his legendary crime saga Breaking Bad. The new show seems poised to explore the deep, uncomfortable relationship between our society and its attorneys in a new way—it’s exciting, unexplored territory.

“You’re the kind of lawyer guilty people hire,” embezzler’s wife Betsey Kettelman tells Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk, who is not yet the “Saul Goodman” from the other show). Her sneering contempt, even in the face of redhanded, conclusive evidence that she fits that description—she is guilty—illustrates our strange, willful blindness to the basic tenets of criminal law, and how its objective framework of evidentiary proof has become a much more nebulous and erratic game of images.

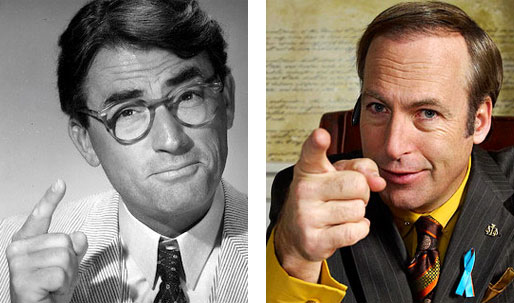

The Constitution guarantees a fair trial, and Americans basically understand and accept this…up to a point. In real life and fiction, heroic lawyers come in two varieties: underdog prosecutors bringing civil lawsuits in David-and-Goliath scenarios—Jan Schlichtmann in Anderson v. Cryovac (the basis for Jonathan Harr’s 1996 bestseller A Civil Action); Paul Newman in The Verdict (1979)—or criminal defense attorneys struggling to exonerate the innocent—Edmund Randolph clearing Aaron Burr of treason charges, or America’s most famous fictional attorney, Harper Lee’s Atticus Finch (from the Pulitzer-winning To Kill A Mockingbird), who famously struggles and fails to defend a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in the Deep South of the 1930s. Gregory Peck, delivering his signature performance in the movie of To Kill A Mockingbird, probably best exemplifies the iconic American “lawyer as hero”—bookish and cerebral, yet passionately devoted to justice, virtue and the rule of law.

But when a criminal defendant is guilty (or is viewed as guilty), the picture changes. Now we’re in the realm of Johnnie Cochran and, onscreen, Tom Hagen (the Corleone’s “despicably loyal” – in Pauline Kael’s phrase—attorney in the Godfather movies). Idealism gives way to cynicism, bitterness, and a deep anti-institutional mistrust: killers and thieves “get off” on “technicalities” while the lawyers who perform this dark magic, we are meant to understand, struggle with deep moral anguish over the ethical sacrifices implicit in defending “those people.” The exoneration of the guilty is viewed as profound social rot—a “system” that is “out of order,” as Al Pacino famously screams at the courtroom in the climax of …And Justice For All (1979), one in a series of cinematic monuments to post-Watergate cynicism. (Public defender Pacino’s redemptive triumph is his exposure of his client’s guilt – the audience cheers as he does literally the worst thing a criminal lawyer can possibly do. As they see it, he’s not betraying the framework of criminal justice, he’s saving it.) Later, in The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Pacino played an attorney who’s literally Satan—and who brags that the law “puts us [the minions of Hell] into everything […] It’s the new priesthood, baby!” going on to extoll how his demonic works lead to “acquittal after acquittal after acquittal until the stench of it reaches…high and far into Heaven.”

Which brings us to Jimmy McGill, the “criminal lawyer” who turns out to be not nearly as trivial or satiric a figure as he seemed (in his comic-relief appearances on Breaking Bad). To the surprise of many, McGill not only has a strong moral center but (in a deft reversal of Walter White’s descent) seems to be consistently gravitating towards good rather than evil. So far, he’s had many opportunities to do the wrong thing, and he’s avoided every one of them.

What’s especially interesting – and thrilling – about Gilligan’s (and Odenkirk’s) new work is how it betrays the Breaking Bad formula. Walter White’s descent into evil (portrayed on an operatic scale rivaling those of Michael Corleone or even Macbeth) isn’t being mechanically reproduced (which many expected), it’s being inverted. White and McGill both begin as losers, but while White finds Nietszchian redemption in darkness and corruption, McGill is already moving towards the light. Yes, he’s an irredeemable sleaze (with a business profile that’s a hilarious, dead-on parody of the worst ambulance chasers ever to advertise on matchbooks); yes, his story is interwoven with Vince Gilligan’s gloriously lurid Albuquerque criminal underworld (where his and White’s fates will entwine). But already, his passions are stirred. Watch him furiously chastise his bored courthouse adversary (in one of a series of sardonically-presented men’s room confrontations) for not even bothering to keep the defendants straight; watch his panicked self-preservation transform into a genuine selfless need to enlist his crazy Clarence-Darrow-with-Tourettes oratorical gifts in the rescue and protection of his lowlife partners-turned-clients.

McGill’s transformation into to Goodman promises to be as thrilling and engrossing as White’s transformation into Heisenberg, but the boldness and daring of Gilligan’s apparent intention to tell the opposite story – to alchemize damnation into salvation – attempts to rewrite the rules of our literary and cinematic fascination with criminal law: the moral shadings are under a kind of microscope that hasn’t been employed before. And in post-9/11, post-John-Woo America, as our growing impatience and fatigue with the obligations of providing a best defense have created a troubling, mob-like, vindictive “victim’s rights” mentality so pervasive that Habeas Corpus itself seems threatened and terror suspects are routinely imprisoned without criminal charges or representation (or subjected to punishments cloaked in Orwellian terms like “rendition” and “enhanced interrogation”), the Albuquerque ambulance-chaser with the pocketful of customized matchbooks may provide a crucial allegory. Saul Goodman (to paraphrase Gotham City’s literally two-faced DA) may not be the lawyer we want, but he’s the lawyer we need.