Author Photo

Sunday, May 3rd, 2015 • Cartoons

Tuesday, April 28th, 2015 • Tech / Writing

Until last Friday, nobody actually owned an Apple Watch except for Tim Cook, who has a custom version with a red crown since the 38 possible variations are inadequate for him; a special one had to be made (Beyoncé and Karl Lagerfeld also have custom solid-gold Apple Watches they were given for free). Nevertheless opinions of the new device have been dispensed everywhere and, in fact, despite a general enthusiam, “inadequacy” is a main theme: not enough battery life; not enough computing power; not enough capability without a “parent” iPhone (as the phone tethers to the PC, the watch tethers to the phone; with there next will be a ring that tethers to the watch?); not enough speed; not enough of that mysterious unnamable quality that makes Swiss watches actually worth tens of thousands of dollars even though they use 100-year-old technology and are therefore not in danger of becoming obsolete (this last part confuses me but this is the claim being made by the Swiss).

But it’s not the Apple Watch that’s inadequate; it’s me. I finally came to grips with this when I sat down to explore all of the device’s capabilities in detail, on Apple’s website. They have a series of short films in which a very chipper person explains, in encouraging tones, how it all works, while we see the phone in that same infinite white Platonic void where all Apple products actually live before they must descend, like Primeval Greek Gods, down into our mundane lives. (Maybe we’re seeing the inside of Jonathan Ive’s imagination; I have looked closely at the smooth reflections in the stainless steel version of the Apple Watch that floats in that white void and can make out nothing of the surroundings.)

The watch has a special button that lets me, immediately, get access to the ten or twenty people whom I must contact so instantly that pulling out my phone is simply too slow. I can then text them (in a rudimentary way; without a keyboard I’m reduced to Paul-Revere-level communication, unless I direct my message through Siri, who frequently has trouble grasping what I’m saying) or I can actually call them by speaking into my wrist like the secret service agents in the movies.

But, who are all these people? Yes, I have a fairly extensive contact list, thank you very much, but closer examination reveals that it’s my dentist, and people like that, who take up most of the space (along with former co-workers and the other people in my building whom I contact about steam problems). There are business contacts, to be sure, but I’ve been finding over the years that Captain-Kirk-style communication with them is sufficient; if I were moving faster every day, or had more people dependent on my immediate feedback about everything (as does, say, the President), then that “dedicated” “hardware” button on the phone would make more sense.

I can also keep track of my investments, literally, with the flick of a wrist; all the beautiful Apple Watch faces can be customized to include a stock ticker. I have trouble remembering the last time subtle Wall Street fluctuations had this kind of urgency for me (mostly I just stare glumly at the readouts of certain web pages, with a vague feeling of regret, like everyone else). Those same watch face customizations let me seize control of my daily calorie burn and workout progress by showing me beautiful rotary displays of energy expenditure and sprinting times. Again, I don’t think I quite measure up to this; if they had one for sandwiches or beer consumed I would be better served (it could tell me when it was time to offer to buy a round).

The Watch has “Taptic Feedback,” which means not just that I can be alerted subtly by means of a “tap” on the wrist, so I can continue reading My Pet Goat uninterrupted; the same mechanism (those introductory films explain) allow me to “pair” my watch with another so that the participants can feel each others’ heartbeats or send each other little finger-swipe-based hieroglyphs like the hearts girls would draw on the edges of notebook pages, in school. Would that there were such a person. The scenario of being invited to feel somebody’s heartbeat happens, shall I say, infrequently enough that the process does not require telecommunications.

Apple had a media event for explaining their watch and invited “a friend” to help demonstrate its utility: Christy Turlington, who’s been making people feel inadequate for decades. The supermodel/philanthropist/scholar got up on stage to introduce a segment describing her important work in Africa and her preparation for the next marathon she’ll run: the Apple Watch, Turlington assured us, has been invaluable. Good. When I do those sorts of things, I keep wishing I had the right gear with me. The Watch’s fitness systems actually “remind” you when you’ve been sitting too long and have to go outside—I think this feature, alone, would drain the battery of mine so fast that the device would be impractical.

So I can’t get an Apple Watch not because I don’t want one but because I simply don’t measure up; my life doesn’t have any of the absences it would fill. I’m not good enough. I think Apple knows about me; there has to be a reason they included the Mickey Mouse face.

Monday, March 9th, 2015 • Writing

America’s dubious relationship with criminal defense, onscreen and off, has hit an interesting cultural speed bump with AMC’s new hit Better Call Saul, Vince Gilligan’s innovative prequel to—and, really, moral inversion of—his legendary crime saga Breaking Bad. The new show seems poised to explore the deep, uncomfortable relationship between our society and its attorneys in a new way—it’s exciting, unexplored territory.

“You’re the kind of lawyer guilty people hire,” embezzler’s wife Betsey Kettelman tells Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk, who is not yet the “Saul Goodman” from the other show). Her sneering contempt, even in the face of redhanded, conclusive evidence that she fits that description—she is guilty—illustrates our strange, willful blindness to the basic tenets of criminal law, and how its objective framework of evidentiary proof has become a much more nebulous and erratic game of images.

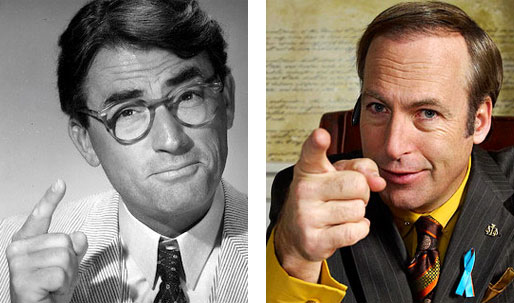

The Constitution guarantees a fair trial, and Americans basically understand and accept this…up to a point. In real life and fiction, heroic lawyers come in two varieties: underdog prosecutors bringing civil lawsuits in David-and-Goliath scenarios—Jan Schlichtmann in Anderson v. Cryovac (the basis for Jonathan Harr’s 1996 bestseller A Civil Action); Paul Newman in The Verdict (1979)—or criminal defense attorneys struggling to exonerate the innocent—Edmund Randolph clearing Aaron Burr of treason charges, or America’s most famous fictional attorney, Harper Lee’s Atticus Finch (from the Pulitzer-winning To Kill A Mockingbird), who famously struggles and fails to defend a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in the Deep South of the 1930s. Gregory Peck, delivering his signature performance in the movie of To Kill A Mockingbird, probably best exemplifies the iconic American “lawyer as hero”—bookish and cerebral, yet passionately devoted to justice, virtue and the rule of law.

But when a criminal defendant is guilty (or is viewed as guilty), the picture changes. Now we’re in the realm of Johnnie Cochran and, onscreen, Tom Hagen (the Corleone’s “despicably loyal” – in Pauline Kael’s phrase—attorney in the Godfather movies). Idealism gives way to cynicism, bitterness, and a deep anti-institutional mistrust: killers and thieves “get off” on “technicalities” while the lawyers who perform this dark magic, we are meant to understand, struggle with deep moral anguish over the ethical sacrifices implicit in defending “those people.” The exoneration of the guilty is viewed as profound social rot—a “system” that is “out of order,” as Al Pacino famously screams at the courtroom in the climax of …And Justice For All (1979), one in a series of cinematic monuments to post-Watergate cynicism. (Public defender Pacino’s redemptive triumph is his exposure of his client’s guilt – the audience cheers as he does literally the worst thing a criminal lawyer can possibly do. As they see it, he’s not betraying the framework of criminal justice, he’s saving it.) Later, in The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Pacino played an attorney who’s literally Satan—and who brags that the law “puts us [the minions of Hell] into everything […] It’s the new priesthood, baby!” going on to extoll how his demonic works lead to “acquittal after acquittal after acquittal until the stench of it reaches…high and far into Heaven.”

Which brings us to Jimmy McGill, the “criminal lawyer” who turns out to be not nearly as trivial or satiric a figure as he seemed (in his comic-relief appearances on Breaking Bad). To the surprise of many, McGill not only has a strong moral center but (in a deft reversal of Walter White’s descent) seems to be consistently gravitating towards good rather than evil. So far, he’s had many opportunities to do the wrong thing, and he’s avoided every one of them.

What’s especially interesting – and thrilling – about Gilligan’s (and Odenkirk’s) new work is how it betrays the Breaking Bad formula. Walter White’s descent into evil (portrayed on an operatic scale rivaling those of Michael Corleone or even Macbeth) isn’t being mechanically reproduced (which many expected), it’s being inverted. White and McGill both begin as losers, but while White finds Nietszchian redemption in darkness and corruption, McGill is already moving towards the light. Yes, he’s an irredeemable sleaze (with a business profile that’s a hilarious, dead-on parody of the worst ambulance chasers ever to advertise on matchbooks); yes, his story is interwoven with Vince Gilligan’s gloriously lurid Albuquerque criminal underworld (where his and White’s fates will entwine). But already, his passions are stirred. Watch him furiously chastise his bored courthouse adversary (in one of a series of sardonically-presented men’s room confrontations) for not even bothering to keep the defendants straight; watch his panicked self-preservation transform into a genuine selfless need to enlist his crazy Clarence-Darrow-with-Tourettes oratorical gifts in the rescue and protection of his lowlife partners-turned-clients.

McGill’s transformation into to Goodman promises to be as thrilling and engrossing as White’s transformation into Heisenberg, but the boldness and daring of Gilligan’s apparent intention to tell the opposite story – to alchemize damnation into salvation – attempts to rewrite the rules of our literary and cinematic fascination with criminal law: the moral shadings are under a kind of microscope that hasn’t been employed before. And in post-9/11, post-John-Woo America, as our growing impatience and fatigue with the obligations of providing a best defense have created a troubling, mob-like, vindictive “victim’s rights” mentality so pervasive that Habeas Corpus itself seems threatened and terror suspects are routinely imprisoned without criminal charges or representation (or subjected to punishments cloaked in Orwellian terms like “rendition” and “enhanced interrogation”), the Albuquerque ambulance-chaser with the pocketful of customized matchbooks may provide a crucial allegory. Saul Goodman (to paraphrase Gotham City’s literally two-faced DA) may not be the lawyer we want, but he’s the lawyer we need.