Monday, January 11th, 2016

•

Writing

A child sits alone at home, a teenager, upset, angry, sad, misunderstood. The bedroom has posters and a barricaded door and may be anywhere in the world; I picture one in Illinois where my grandfather was born, the smallest town I’ve ever seen and the place he escaped from in high school to drive a cab in Chicago. Or I picture Chicago, where I went to college and listened to Bowie, over and over alone or with my friends, or London where Pete Townshend locked himself in his bedroom with his guitar and imagined the series of young anguished boys dreaming of the sea off of Brighton, of the William Blake mystical world beyond the mundane reality of teenage wildlife, the joy of the Liverpool kids when their idols returned from America and played the Cavern for the last time.

The teenager in the bedroom, listening to records, maybe crying, maybe drunk, ears stinging from the shouts of parents and teachers, dreaming of a girl or a boy, hoping to someday escape—has anyone, ever, in the history of music or art, ever spoken as urgently or beautifully or intelligently or life-savingly to him or her as David Bowie?

“Give me your hands, ’cause you’re wonderful,” Bowie insists at the magnificent ending of Ziggy Stardust (the quiet opening of the last song, “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide,” that leads to the deafening, insistent crescendo, strings and horns over raw acoustic guitar). “If the homework brings you down/Then we’ll throw it on the fire and take the car downtown,” he reassured me slyly on Hunky Dory, where he also sang about Warhol and Dylan. I’m moved to tears as I remember my first cup of black coffee, my first cigarette, my last cigarette, my life described as a road that began in a small room with posters and parents outside and music that saved me from despair, from being alone, and that music was Bowie’s. I “ran away from home” in high school after smashing some crockery and showed up at a girl’s house and cried and we listened to Bowie while my father prowled the New York streets on a bicycle asking doormen if they’d seen me—that time it was Aladdin Sane; Robert Christgau wrote, “This music can help you through the harshest realities,” and he was right.

I came late to Bowie’s career, or, it seemed like that at the time: Let’s Dance, those baffling songs with the horns and gunshot-drums of the 1980s, the angular pastel graphics from the Reagan years; the suits and suspenders and bleached hair that were mercilessly ridiculed in Velvet Goldmine, decades later, the beautiful, studied mindlessness of that record (and the Cat People song that, it turned out, Tarantino remembered too, superimposing it over his WWII fantasy, which, I think, Bowie probably liked) that dismayed his long-time fans and ignited our bloodstreams on MTV, and the Stevie Ray Vaughan guitar lines—so different from the Jackson-Pollack slashing guitar of Robert Fripp (on Scary Monsters), whose solos give you paper-cuts on your heart. “Blue Jean,” later, in college, and Tin Machine and the remaining two decades of crazy brilliance that we didn’t know lay in wait; the Somalian supermodel wife, the movie roles (he has a knife fight with Carl Perkins in John Landis’ forgotten, charming Into the Night in 1982). Discovering the older records, learning from Bowie about Jean Genet (the “Jean Genie”) and William Burroughs and Orwell, about love and death and strangeness and the certainty of not being alone even when it seemed irrefutable that nobody understood you at all and nobody ever would.

Throughout all of it there’s the incredible artistry, that operatic, sandy, infinitely wise and sensitive voice on track after track, a voice that could move like Olivier’s or Pavarotti’s and whisper like Lou Reed (whom he produced, and wrote for, and loved as a brother) or like Leonard Cohen, but which was always unmistakable; always his. The young lovers collide by chance, reach for each other, nearly blow it all, but are saved by the strength of their minds and their hearts. “We’re absolute beginners, but we’re absolutely sane,” Bowie sang, through the voice of another of his fragile, lost, damaged but ultimately tough-as-nails teenagers. In his greatest song, a man and a woman share a kiss beneath the shadow of the Berlin wall: “the shade” is “on the other side,” but they can be heroes just for one day.

Berlin was where Bowie found his deepest inspiration, his strongest muse, retreating there in the miasma of the late seventies, bringing Brian Eno with him in his escape from the white cloud of cocaine he’d become mired in during his Los Angeles years, the years he made records like Diamond Dogs that he didn’t even remember writing or recording. Bruegel went to Italy and made four paintings that changed the course of Western art; Bowie made three records in Berlin (and a fourth, two years ago) that changed rock’n’roll. That constant movement forward, all those “Changes,” that perpetual dissatisfaction that’s the secret to art, was Bowie’s great strength (I’m sure the Internet is filled with the word “chameleon” this sad morning, as well as clever wordplay about “falling to Earth”). But it was his endurance, his fierce refusal to abandon the vital essence of his music, his perpetual understanding of the fundamental youthful spirit of rock’n’roll as he aged, that makes him timeless, that makes him immortal. In Bowie’s hands, rock’n’roll became sublime, elevated among the highest arts; I am alive, I am quite sure, because of his music and the despair he saved me from in those years, and somewhere right now an angry teenager is listening to Bowie and the pain is receding. (“Because you’re young,” Bowie sang in 1980, “you’ll meet a stranger some night.”) May his voice live on, for years and decades to come; may his records be blasted from bedroom speakers wherever or whenever a lonely soul needs comforting, whenever or wherever a strange boy or girl needs to feel, not ashamed, but proud and defiant in the face of life’s pain. We won’t see his like again.

Friday, December 18th, 2015

•

Movies / Writing

A true Jedi makes his or her own lightsaber—and a true Star Wars fan makes his or her own Star Wars. I never expected to create my own versions of the original trilogy, but in 2010, that’s exactly what I did.

For George Lucas, Star Wars has been, over the decades, a moving target, a changing daydream reflecting his ongoing fascination with film technology and with the evolving mythos inside his head, inspiring him not just to re-craft the old movies into the almost-universally-hated turn-of-the-century “Special Editions” (which presaged the profound wrong turn of his Prequel Trilogy) but to withdraw the originals, outraging the fans whose need to see Han shoot first led first to thousand-name online petitions, demanding that the unaltered versions of the original movies be restored and re-released, and then to an incredible wealth of labor by the film geeks who have painstakingly “De-Specialized” the trilogy, re-assembling simulations of the original versions and circulating them on websites like fanedit.com and originaltrilogy.com.

Yes, I am embarrassed to admit, I did this: five years ago, while deep in a mid-winter depression, I followed the links to those sites and began making “my” Star Wars: like William Alland’s faceless 1941 journalist searching for Charles Foster Kane’s true story, I embarked on an act of cinematic retrieval that led deep into the past, and straight to the heart of my childhood. In order to explain why, I have to recall the saga’s deep roots, not in any eternal cinematic mythos, but in the 1970s and 1980s. For me, and for my generation of fans (which includes J. J. Abrams), the movies are irrevocably tied to the deepest fabric of the years they were made, and to who we were, back then: like Kane’s boyhood sled, recalled decades later, they are playthings turned into monuments; they carry an indelible watermark of the past.

On an afternoon in the last week of April 1977, I walked to Farrell’s candy store around the corner from my school and saw a small, glossy, creased poster taped to the glass door: a minimalist advance promo flyer of unadorned navy blue with four lines of white Serif Gothic type* that read “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” above the now-iconic line-art title treatment and the original, art-deco 20th Century Fox logo—the only other graphic element, I vividly remember, was the prominently featured symbol for the mysterious, cutting-edge “Dolby System” I’d seen in magazine ads for stereo equipment. I was eleven years old and a science fiction fan, which enlisted me in a private society; I had no idea that my shameful, secret fascination would, over the following decades, become as mainstream and accepted as baseball or rock and roll (or disco, I would have automatically added) or that the instrument of that breakout was right in front of me that late spring afternoon.

There were other stirrings of something big: Marvel Comics had been running crazed, postage-stamp-sized advance ads in all their titles over the previous few months, promoting their (unprecedented) tie-in adaptation of what they called “The Greatest Space Fantasy Film of All”—I had heard similar, third-hand hyperbole from attendees of recent sci-fi and Trek conventions, and, weeks before, seen an older boy on the crosstown bus reading a rack-sized paperback called Star Wars by somebody named George Lucas (the famously bank-breaking novelization ghostwritten by industry journeyman Alan Dean Foster) with an unsettling, dream-like cover painting of a man with a glowing sword, two mismatched robots, and a looming iron mask filling the sky behind them—one of the famous early commissioned paintings by aerospace industry illustrator Ralph McQuarrie that, we now know, were the instrument by which 20th Century Fox executives like Alan Ladd, Jr. were persuaded to spend ten million dollars on “that space movie.”

Even those of us attuned to these signals had no idea what to expect: we lived in a starved pre-geek world of nightly Trek reruns (coming in over TV aerials) and pedestrian, shopping-mall-for-the-soul embarrassments like Logan’s Run and Westworld and Fantastic Voyage. The seeds of a majestic lineage of cinematic sci-fi had already been planted, tracing from Stanley Kubrick to Gerry Anderson’s Space: 1999 (the tech artists of each who would end up at ILM, Lucas’ legendary private effects fiefdom)—a new kind of poetic, post-NASA technical realism that would reach its baroque fruition that summer, replacing the worn-out tropes of Irwin-Allen/Aaron Spelling fantasy as swiftly and completely as Lorne Michaels replaced Johnny Carson—but we knew nothing about that. We didn’t know where we were in the flow of history that seems so indelible now: we didn’t know what would happen to Bruce Jenner or O. J. Simpson or Robin Williams or Bill Cosby or the other magazine-cover fixtures of our time; we didn’t know the fates of Michael Jackson or Richard Pryor or John Denver or Farrah Fawcett-Majors or John Belushi or John Lennon. Some of us had heard of Steve Jobs; Richard Nixon was still in San Clemente and would not find Manhattan real estate until two years later; Truman Capote and Calvin Klein rubbed shoulders with John DeLorean and Henry Kissinger at Studio 54; posters of Travis Bickle standing before his taxicab in the dark urban gloom had scared me just months before.

Decades later, taking the commercial DVD of Star Wars apart on my computer—or rather, extracting and doctoring the sequences that Lucas’ 1997 digital team had enhanced, in an effort to undo their efforts and “de-specialize” the movie—was an exercise in reverse archeology; like restoring a damaged painting by adding, rather than removing, debris. For every shot, there are archival elements (including retrieved vintage stills, old laserdisc and VHS copies, and even scratched, faded, and meticulously scanned and restored 16mm and 8mm editions) that have been mined and distributed by the tireless originaltrilogy.com archivists. (“Popular Downloads” include a high-res image of the original, pre-tilt opening crawl text for each episode.) And, even amongst these self-taught archivists, there are fierce differences of opinion: the adherents of one school of thought, for example, prefer the amped-up color mix of the newer DVDs, despite its infidelity to the original release, while others debate the merits of different stereo and six-track soundtrack mixes (one downloadable edition of the trilogy has twelve separate audio programs, incorporating every possible version of the audio mix including a music-only track).

What emerges from this backwards excavation, as the additions to the famous scenes are painstakingly covered over—as the CGI dewbacks and rontos and digital crowds disappear, revealing the original, sparsely-occupied Mos Eisley sets; as the final space battle reverts to its original, simplified form; as the Millennium Falcon rises skywards offscreen (rather than in a jarring CGI shot that already looked dated five years ago); as Jabba the Hutt remains an unseen figure; and, yes, as Han shoots first—is the astounding artistry of this exuberantly analog artwork: the actors banging wooden sticks together beneath reflected beams of light that comprise the swordfights; the guns that fire hand-drawn cel animation, the “laser blasts” painted frame by frame; the full-sized wooden spacecraft that cannot move, suspended by ropes and pulleys, and, over all of it (along with Williams’ allusive score) the dense tapestry of sound; the hammers hitting miked California highway suspension cables to create the blaster noises and the blend of animal growls that comprise Chewbacca’s howls, along with the thousands and thousands of other elements on Ampex magnetic tapes that come together to create that post-Phil-Spector, post-Beatles “wall of sound” comparable to Orson Welles’ best radio work. Frame after frame are filled with painstakingly hand-animated, “claymation” stop motion (more than in King Kong or any other Ray Harryhausen epic), and everywhere you look are invisible sheets of glass; the hallucinogenic matte paintings that fill in the backgrounds of shot after shot (The Empire Strikes Back has 45 matte paintings, providing not just the rebel hangar and its surrounding snowscapes but the entire “cloud city” of Bespin, a mirage built, like Welles’ “Xanadu,” almost entirely of hand-brushed acrylic paint—with, on several occasions, three or four paintings providing different vantage points on the same imaginary locales, including the German-Expressionist balustrade where Luke and Vader have their penultimate confrontation).

Ironically, given the storyline, there are no computers involved in the production at all; all the onscreen tactical displays are handmade animation, and the robots speak in distorted human voices and whistles. (The only computer-generated onscreen content is the primitive, Pong-level vector-graphic of the Death Star approach shown to the Rebel pilots, preparing the audience for the tour-de-force final sequence—“you are required to move down this trench to this point […] only a direct hit will trigger a chain reaction”—that presages the frameworks, environments and scenarios of PlayStation/Xbox “levels” that wouldn’t be available or even comprehensible for decades—Star Wars is the very first movie to intrinsically work like a video game.) And yet, the story is full of computers; the main plot of the 1977 movie is essentially a pre-Snowden tale of an errant email attachment (the “old data” digital hologram Artoo Detoo shows to a smitten Luke Skywalker, setting the plot in motion, that’s actually a superimposed picture-tube television image). Throughout, Lucas presents a reflection of the 1977 world, with its Casio digital watches and Radio Shack “home computers,” poised on the brink of globalism and technological revolution; his filmmaking team’s wood and paint and wire and glass comprise a forbidding but romantic “Future Shock,” an epic, analog vision of the digital world to come that paints it as a lost landscape that we already seem to know.

And along with the ersatz computers, Lucas’ vast, imaginary universe is filled with tall tales and exaggerated falsehoods, both verbal and visual; the “ion cannon” and the “cloaking device” and the “garrisons” and “blasters” and “regional governors” and “diplomatic missions” and other words that mean nothing beyond their suggestive sounds; the exaggerated statistical numbers (a hundred star systems, a thousand generations); spacecraft the size of cities and “battle stations” the size of moons with “docking bays” large enough to enclose the pyramids that are just more acrylic-covered panes of glass—George Pal or Gene Roddenberry would have understood (and explained) what powered those engines and guns, how those governments and societies worked, what this “period of civil war” is all about, but Lucas knows (or, knew) that it doesn’t matter; that it’s all elemental and sensual, making no sense beyond the ferocious noise and rushing forward motion, the industrial light and magic.

Of course, as everyone now understands, Star Wars a perfect storm; a once-a-century juxtaposition of cultural, historical, sociological, political and spiritual forces and drives that define the era’s hinge-point, the apex of the arc that leads from World War II to 9/11 and the violent birth of our new millennium—but, more directly, it’s a seismic re-definition of cinema, on the granular level: when you take the Academy-Award-winning cuts apart** and examine the pieces you find not just a clever music-hall fraud—a wood-and-glass, vacuum-tube simulacrum of an incipient technological world—but an artwork that’s all surface; that has no “depth” beyond those elemental dream states, Luke’s severed hand and endless fall, Ben’s resurrection as a vision projected against the snowscape, Leia and Han’s desperate kiss as they are pulled apart by stormtroopers in that orange and blue, steam-and-steel cauldron at the heart of the floating city.

As fascinated as Lucas has always been with the byzantine internal logic of his mythological saga—what Tolkien called a ‘feigned history’—what’s important isn’t the falling Republic or the rise of the Empire, but that particular cinematic moment, and the exuberantly sensual filmic elements of that time: the lightsabers whose sound is a recording of the USC film projectors Lucas studied with; the booming retro-classical John Williams score; the robed desert figures (Alec Guiness and “the sandpeople” conjuring a child’s view of Lawrence of Arabia); the electrifying documentary-style camerawork and tumbling-dice cutting technique that Lucas developed as a utility cameraman on Gimme Shelter and under Francis Ford Coppola’s tutelage on his first, brilliant pop-art piece, American Graffiti. By repeating the boldly abstracted steps of Graffiti, willfully divorcing himself from the conventions of the immediate cultural past—rejecting the nihilism of Bogdanovich and Cassavettes and Arthur Penn while retaining their technical prowess in order to conjure his “galaxy far, far away”—Lucas created a work of art whose eternal value, like that of all masterpieces, is tied indelibly to its historical moment.

Star Wars, despite its abstractions, its studied timelessness, its Joseph Campbell pretensions, its postmodern lineage, is a fixture of its era: it may seem to be about the past—about decades of movies or centuries of myth and legend—but it’s really about its own year, about the rush of the ’Seventies after Watergate and Vietnam (where bodies were incinerated beneath the open air, like Luke’s aunt and uncle with their Tupperware and denim clothes), about New Hollywood, about Jimmy Carter and the Shah of Iran, about Warhol portraits and Sony Betamaxes and Atari games, about the boomer generation coming of age on the eve of the Reagan years and taking over the culture and the world, about the birth of the American summer blockbuster as the lingua franca of global imagination and desire. It’s about the coming turn of the century, about robots and computers (although the only computer involved in its creation was the hand-built logic board within John Dykstra’s groundbreaking Dykstraflex motion control camera); it’s about the coronation of cinema as the primary modern art form and science fiction as the primary post-industrial, postnuclear storytelling mythos. And, as the world learns today—and as I first suspected when J. J. Abrams joyfully presented his fake Topps-bubble-gum “trading cards” for the new movie, exactly duplicating the originals that I collected at Farrell’s candy store around the corner from my school—that mythos is less about George Lucas’ “galaxy far, far away” than about that vanished world of 1977—that fragile, hopeful, “long time ago” that we’ll never forget.

* The logo and artwork for The Force Awakens brilliantly resurrects that same font, as well as subtly rounding the logo’s edges to approximate the blurry lithography of that time.

**Star Wars was edited by Richard Chew, Paul Hirsch and Lucas’ wife, Marcia, who also cut Taxi Driver.

Monday, August 17th, 2015

•

Writing

This weekend I got immersed in an arbitrary grouping of three books, of wildly varying quality: Renata Adler’s stunning After the Tall Timber (2015), a retrospective of nonfiction writing (from The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, Harper’s, and other publications), Ellin Stein’s lively and perceptive That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick (2013), a reported history of National Lampoon and its cultural progeny, and A. E. Hotchner’s mediocre but gold-dust-strewn Blown Away: The Rolling Stones and the Death of the Sixties (1990), which purports to discuss “theories” about Brian Jones’ death but actually reheats and garnishes long-available fare from the perpetual steam table of Stones-related interviews and criticism.

This was all totally random and serendipitous. I discovered the Hotchner while wandering through the (beautifully reconditioned) third-floor galleria of the Town Library in Lenox, MA, and I found the Stein through my own research into the Lampoon, of which I’ve been a fan for decades, whereas the Adler was pressed into my hands by my father, who ordinarily detests celebrity journalists—I lent him Adler’s acetone-soaked Speedboat (1976), winner of the Ernest Hemingway Award for Best First Novel, in response. The rest of Adler’s résumé is just as pain-inducingly impressive; in fact, just to masochistically get it over with and wallow in the burning jealousy I’ll just reprint her whole bio:

Renata Adler was born in Milan and raised in Connecticut. She received a B.A. from Bryn Mawr, an M.A. from Harvard, a D.d’E.S from the Sorbonne, a J.D. from Yale Law School, and an LL.D. (honorary) from Georgetown. Adler became a staff writer at The New Yorker in 1963 and, except for a year as the chief film critic of The New York Times, remained at The New Yorker for the next four decades. Her books include A Year in the Dark (1969); Toward a Radical Middle (1970); Reckless Disregard: Westmoreland v. CBS et al., Sharon v. Time (1986); Canaries in the Mineshaft (2001); Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker (1999); Irreparable Harm: The U.S. Supreme Court and The Decision That Made George W. Bush President (2004); and the novels Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983).

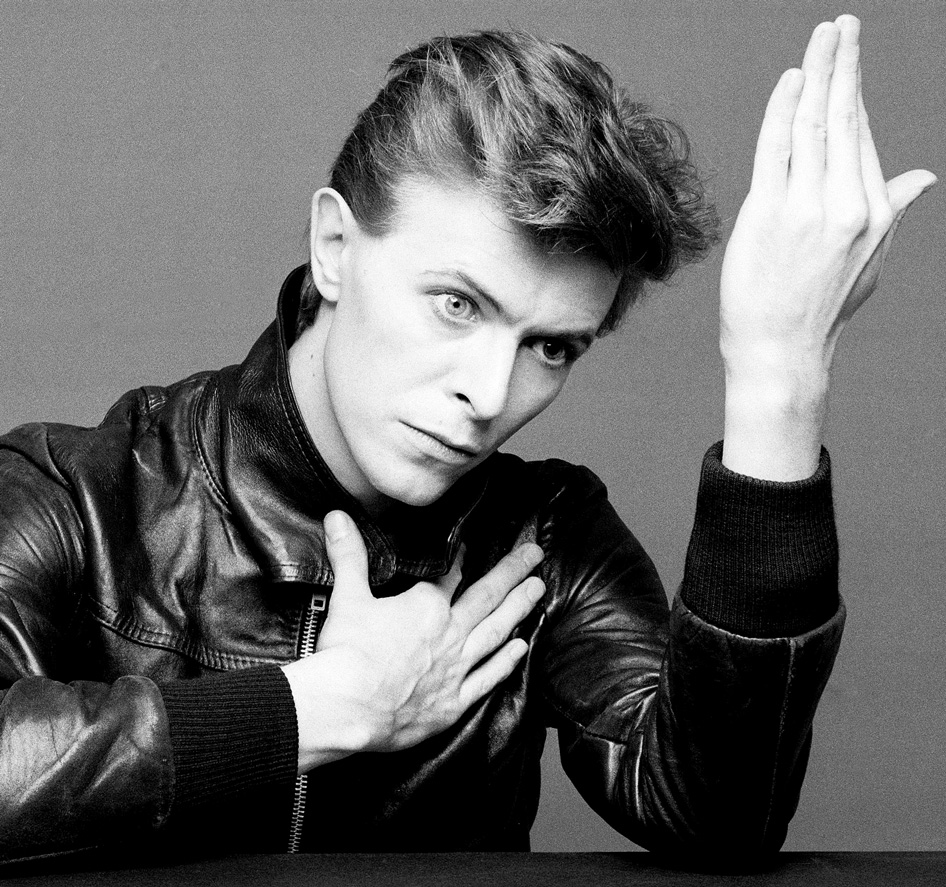

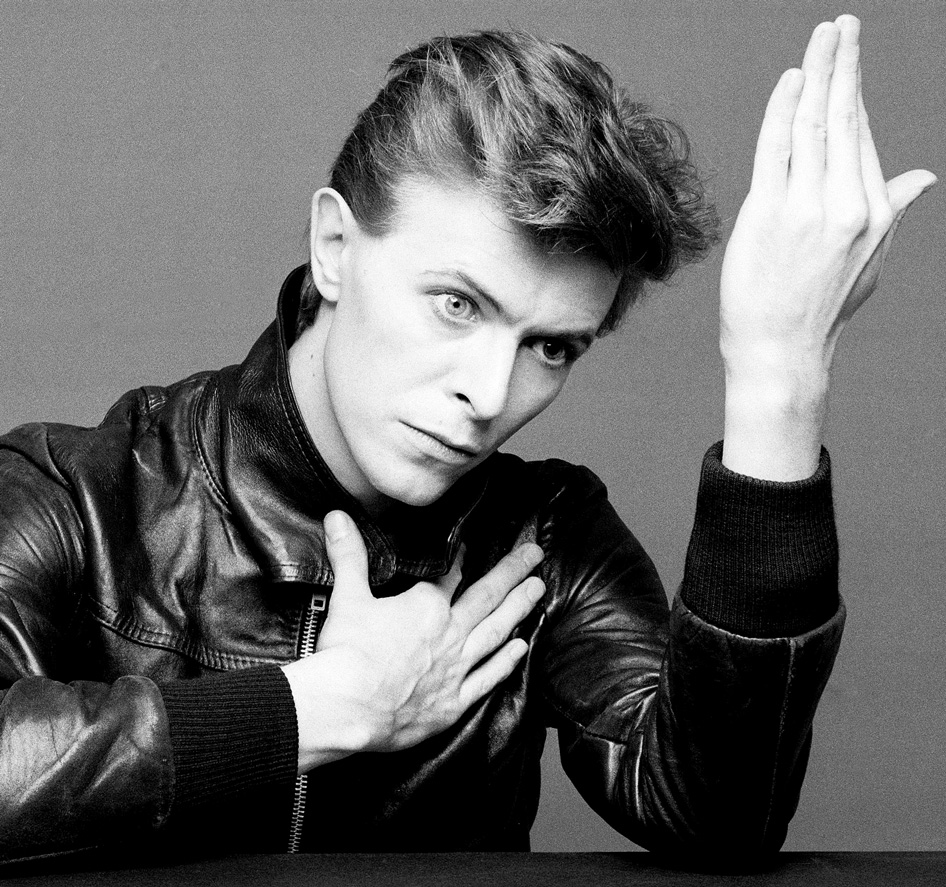

We might as well all just give up and go home. The bio doesn’t even mention the famous Richard Avedon portrait (above left) or the breathless, catty, awestruck way she is discussed, as in, for example, Michael Wolff’s unabashedly worshipful preface:

I was at a cocktail party on Manhattan’s West Side at the home of a New York Times cultural supremo attended by a set of publishing myrmidons of frightening standing and lockstep opinions. Following the whispered name “Renata,” I literally intruded on a clucking circle of these reproachful men planning their counterattacks against her: something must be done. The writer Harold Brodkey, her friend and colleague at The New Yorker, once said to me, in the 1970s when she was having her famous and glamorous moment, that in his view, Renata could not decide whether to live an “interior writer’s life” or “an exterior activist’s life.”

Right; that must have been tough. But what interests me especially is the specific context of the anecdote: Wolff explains that these “myrmidions” are reacting to Adler’s 1999 excoriation of The New Yorker right after its sale and “head transplant” (when Tina Brown, coming from Tatler and Vanity Fair, replaced Robert Gottlieb as editor there), but that’s just the beginning of the sexy controversy. I spent hours this weekend going through Adler’s “A Court of No Appeal,” a 2001 essay so sharp and brilliant and complex that I had to slow myself to a near-preschool reading speed in order to absorb what she was saying, which goes well beyond a discussion of any one periodical. Adler starts that essay with the same “canary in a mineshaft” metaphor she used later that year to discuss Kenneth Starr and the dissolution of reasonable standards of judicial discovery: the chain of logic leads from Adler’s New Yorker critique, and its (enormous) repercussions, to a line in that book about Judge John Sirica, who prosecuted the Watergate hearings, to the explosive reaction to that sentence, to the eight separate “hit pieces” that the Times published in the next two weeks, demanding that Adler “retract” her statement, which she refused to do, choosing instead to exhaustively illuminate her original description of Sirica (as “a corrupt, incompetent, and dishonest figure, with a close connection to Senator Joseph McCarthy and clear ties to organized crime”). What begins as a condemnation of The New Yorker evolves into a labyrinthine and devastating critique of not just Sirica and the Times but of the entire modern journalistic apparatus:

The Times, financially successful as it may be, is a powerful but, at this moment, not very healthy institution. The issue is not one book or even eight pieces. It is the state of the entire cultural mineshaft, with the archcensor, still in some ways the world’s greatest newspaper, advocating the most explosive gases and the cutting off of air.

Something has been destroyed; something precious and vital is lost. When you look at the Avedon picture (and are reminded of his portraits of Truman Capote or the David Douglas Duncan candids of Picasso) you feel the pang of the spectator who’s evesdropping on a party that’s already ended: you’re deprived even of the voyeuristic envy that’s pretty clearly the intention of (say) Vogue’s achingly stylish and perfectly accessorized March cover shoot of Taylor Swift and Karlie Kloss, putting their foreheads together for selfies in front of an antique silver Airstream trailer parked amid the sand dunes. At least that stuff is happening now; there’s still a chance to get out into the desert and join them. But Adler’s “moment” is gone, and that’s what Adler’s writing about—that’s the point: it’s over, and you missed it.

The other two books are more obvious about painting the same picture. Hotchner’s frenzied Stones narrative—in which he subtly demarcates recycled interview material by indicating that “Bill Wyman has said” (as opposed to Marianne Faithfull who “says” things directly to him, in his newer interviews that go on far too long)—is called The Death of the Sixties, in so many words. The biographical pattern is eerily similar to Stein’s Lampoon narrative (already recounted from the inside, in Tony Hendra’s 1988 Going Too Far and Rick Meyrowitz’ 2010 Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead): three naïve but ambitious young students meet, in the 1960s (Mick Jagger, Brian Jones and Keith Richards at art school in London; Harvard Lampoon contributors Henry Beard, Doug Kenney and Robert Hoffman in Cambridge); they connect with an impressario who knows the business (record producer Andrew Loog Oldham; publishing mogul Matty Simmons); after some fumbling, they explode into popularity; one of the founders wanders from the true course, is passively expelled by the others, and dies in mysterious drug-related circumstances (Brian Jones in his swimming pool in 1969; Doug Kenney in a hiking accident in Maui in 1980); the survivors carry on, but something crucial has been lost…and, finally, the whole thing is pretty much over. (Kenney is probably best remembered as the co-author of National Lampoon’s Animal House, the most successful comedy in history when it was released in 1978, in which he also played the role of “Stork.”) After the co-founders’ death, the Lampoon could not continue, according to Stein:

Starting in the ’80s, it seemed the Lampooners themselves couldn’t do it anymore, at least not with the same brio, even had they wanted to. The specter of mortality had fatally tempered the arrogance required to bring it off with style, and Kenney’s death had demonstrated that joking about terrible things would not stop them from happening. No matter how fast and slashing your repartee, Fate, God, Chaos—call it what you will—would have the last laugh.

In each case, then, the specific tragedy is connected not just personally but thematically and historically to the passing of an era—Hotchner, in particular, works very hard to explain that not just Jones but the entire edifice of the 1960s counterculture has vanished:

As the seventies progressed, as the Vietnam War ended and Nixon resigned the presidency, the students’ protests abated and with them what remained of the throb of the sixties […] And just as they had mirrored the rise of the madcap sixties, so now the Stones were beholden to its fall. The glitter generation no longer glittered and the Glimmer Twins, Mick and Keith, no longer glimmered.

Hotchner is writing in 1990, exactly halfway through the 50-year history of the Stones. National Lampoon lasted another 18 years after Doug Kenney’s death, and its descendants—The Onion, Bill Murray, Stephen Colbert—illuminate the contemporary scene exactly according to the Lampoon’s template. The New Yorker is as strong or stronger than ever. But it’s not the same, we are told: something crucial has vanished; the party is over, the essence has been lost; the “moment” for all three (or four, if you count Adler’s condemnation of the Times) is gone. Stein’s book concludes with a “where are they now” Afterword that recalls the glum, funereal tone of the closing titles in GoodFellas or American Graffiti—some are dead (Kenney, John Belushi, Harold Ramis); some are going strong (Bill Murray, P. J. O’Rourke, cartoonist Roz Chast) and some have faded to obscurity. The same effect obtains in Hochner’s book, peppered through his interview text: ex-Stone Mick Taylor (who left the group in 1962, just before it exploded) says

Once I left the Stones, I was able to concentrate on getting into the Royal College, but the sad fact was I didn’t get accepted. So if I had stayed with the Stones I could’ve been a millionaire or flat on my face at the bottom of a swimming pool—that’s what I always say. But looking back on it, no doubt I made a wrong decision, not because of the money and fame, but because it was what I really wanted to do […] and sometimes, when I’m driving around in my lorry, making deliveries, I think about what might have been.

Departure, regret, loss, and bereavement, filtered through an elegiac memory of arrival and beginning (as in Joan Didion’s immortal “Goodbye to All That”) is the theme of all these stories, and so many more—really, all the chronicles of cultural, political and artistic serindipity and communal creation. Like Nick Carraway crossing over onto Gatsby’s property, uninvited, after the fact, we return to the trampled fields after the tents are struck and find the discarded fruit rinds and lost flatware from the party; we are too late even to be voyeurs. Where is the next thing? Where can we go be part of a new beginning, like Lou Reed and Edie Sedgwick showing up at Warhol’s factory; like John Reed arriving in Moscow on the eve of the revolution; like the heady days of the Paris salons or CBGBs or Steve Rubell’s Studio 54 or the Athenian Symposium or Kennedy’s White House? Where will tomorrow’s spark ignite, and can we be there at the start and last long enough to tell everyone else, years later, what was created and abandoned, and what they missed?