Thursday, December 29th, 2016

•

Politics / Writing

Despite the joy of seeing beloved family members, I returned from Grosse Pointe, MI this week even more depressed than I’d been at any point since the election, since the casual, obscene racism and unthinking Trump support I encountered (among perfectly well-meaning and pleasant well-to-do Americans who sincerely believe themselves to have the best interests of our nation at heart) was so profoundly debilitating—one of my cousins, a very nice person whom I like very much, impressed upon me the significant narrative of some Vietnamese small business owners “who work really hard” (with all the implications of the phrase that Republicans always call forth) and wanted me to understand that these Vietnamese acquaintances have done well for themselves despite their fundamental disadvantage. “Because they’re not white?” I asked. No, my cousin answered—because they’re not black.

My smiling, innocuous, perfectly decent, heart-of-gold cousin spent the next half hour working to discredit Obama’s academic credentials—sure, he was editor of the Harvard Law Review and a professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Chicago—a school I know something about, since I went there, which of course meant nothing to my cousin—but who am I to give credence to these rigorous metrics? How do I know whether they’re right? The implication—that this is all “hand-outs”—that the academic rigor of Harvard and Chicago is meaningless when it comes to black people—was not lost on me, although my cousin denied the charge throughout. (A subsequent evening, this cousin, along with another, fervently impressed upon my father—an immigrant and U.S. Marine who remembers Roosevelt’s National Recovery Administration’s stickers in his New Jersey windows during the Great Depression—the importance of recognizing the conspiracy between Democrats and African Americans to exchange ill-gotten “free stuff” for votes.)

So, notwithstanding my genuine affection for my extended family, it was with great relief that I returned to my own glorious melting pot of New York City, where the air is not filled with the stultifying deadness of wall-to-wall white people…and, just in the nick of time, to receive my sister’s generous Christmas gift of the complete Blu-ray edition of The Wire. After just two episodes, I could feel the oxygen returning to my soul. My boundless gratitude to David Simon, whose fearless vision of the real America should be remembered for all time. The eternal drama of Baltimore and of all American cities, going back to Ralph Ellison and the IWW and Upton Sinclair, and the black people who so frighten my lily-white, sheltered, beloved extended family with their fantasies of oppression and disadvantage, are immortalized in Simon’s Shakespearean, Dickensian drama, as is a heartwarming reminder of the delicacy and nuance with which some people (Simon was a newspaper journalist, his writing partner a homicide detective) can still perceive the complexity and heroism of American society. Art fights ignorance, as it has since the days of Homer and Chaucer. Entering the frightening new year, I maintain my utopian idealized fantasy that we can still, despite all evidence to the contrary, learn to overcome our base fears and make sense to one another as Americans and survivors. Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.

Tuesday, November 29th, 2016

•

Design

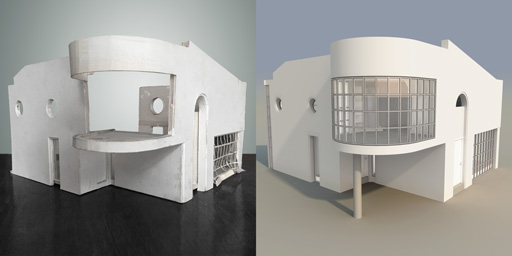

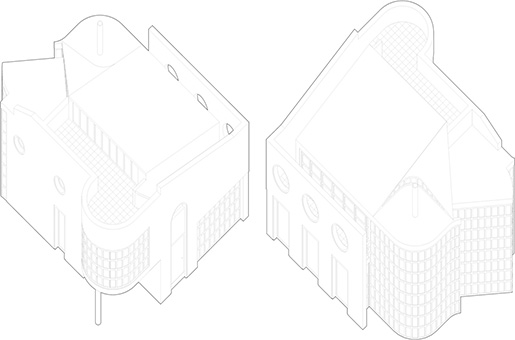

My first full-scale architecture project started in Robert Meredith’s Advanced Architecture class in high school, wherein eight or nine students were given a final assignment of conceiving a small-to-midsize dwelling and executing a certain number of drawings—all done by hand, with pencils and Koh-i-Nor Rapidograph pens on vellum—and an optional model which I attempted but did not complete (below left). My design was heavily influenced by Le Corbusier and by Philip Johnson, and, to a lesser degree, by the contemporaneous “Hi-Tech” stylistic movement which inspired me to hang industrial steel catwalks across the living room (see images below).

1983 model (foamcore, cardstock, mylar); 2016 model (digital) (click for larger view)

That summer I got my very first job, at Peter Eisenman’s firm. Eisenman, one of the “New York Five” architects (along with Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey and John Hejduk) who had come to great prominence and notoriety thanks to an influential 1970 Museum of Modern Art exhibit (curated by Philip Johnson) and an accompanying book, Five Architects (1972), had just won the competition for Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts, his first major non-residential commission and the first large-scaled implementation of his influential principles of “Deconstructive Architecture.” I spent two summers working for Eisenman, assisting on drawings and building charette models for the Wexner Center and other projects (including an unsuccessful Trump proposal that involved my carrying a Plexiglas model ten blocks up Fifth Avenue to Trump Tower, and the future-President’s outer office) and would have pursued an architecture career had I not sold my first novel while in college.

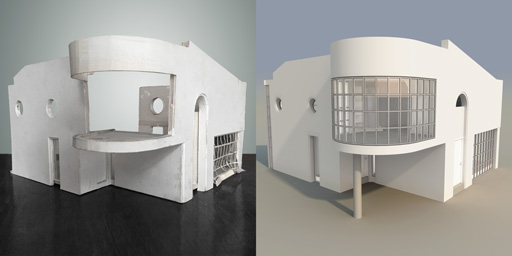

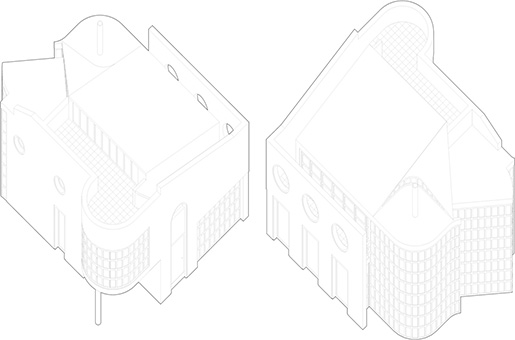

Front and rear axonometric views (1983, 2016) (click for larger view)

When I first met Peter, I showed him the “Meadow House 1” drawings (I was mimicking the Eisenman practice of numbering houses, which Tom Wolfe ridiculed for stripping away all traces of the clients’ identity or relevance—in his From Bauhaus to Our House (1981), he excoriated Eisenman’s essays as achieving “perfect obscurity”), and he took my drawings around to the other architects, saying “Look what this kid did, with no knowledge” (a backhanded compliment that I still treasure). Eisenman said he especially admired the originality and quirkiness of the design, and gravely informed me that, as I advanced upward in the discipline of architecture, my ability to conceive this sort of unusual structure would be systematically diminished over the coming years as summer jobs and postgraduate training leeched away whatever personal vision I might have had, forcing my work into a more and more doctrinaire mimicry of the prevailing trends of the time. (Eisenman’s iconoclastic negativity was consistent as long as I worked with him, as was the densely rigorous academic framework from which he disdained the architectural academy; he would, in the next few years, collaborate with Jacques Derrida on projects for the Venice Biennalle.)

Interiors (from the 2016 digital model) (click for larger view)

Decades later, when I started doing animation (beginning with my Buehrig Design project, a commissioned museum gallery exhibit for which I digitally reconstructed my grandfather’s 1938 Cord Beverly luxury-car masterpiece so as to explain and illustrate his groundbreaking paper-to-clay-to-steel 3D-design techniques), I excavated the Meadow House 1 drawings and model for the purpose of building a full-scaled digital model, which I finished this summer. This new project split into two stages: completing the abstract design (meaning, the nine drawings that convey the idea) and the detailed conception and execution of the model, which was significantly more involved and difficult. For that second part, I worked out the steel-and-concrete support structure of the building (which I’d ignored in high school) and researched modern curtain-wall technology (with double-glazed glass, etc), since I’d decided to execute the design as it would be done if built today—I used contemporary lighting and bathroom fixtures, door/window/cabinet hardware and kitchen appliances (based on the downloadable models and schematics which are now commonplace on houseware manufacturers’ websites).

Now that I can finally see the design in three dimensions, inside and outside, I think it fulfills its modest ambitions (which was not the case with my second Meadow House project, created four years later while I was in college and, as Eisenman had predicted, burdened with a far more slavish and unoriginal design ethos as the dubious “Post-Modern” architectural and aesthetic movement held me in greater and greater thrall). This house, like the early-20th century landmarks that inspired it, would be difficult and expensive to own and occupy—the internal climate would be nearly impossible to frugally maintain, and the stucco/concrete walls would quickly become streaked and stained as happened chronically with Bauhaus-era buildings. Still, it’s a respectable pure-modernist structure, obeying—for the most part—Cobusier’s five points of architecture and essentially upholding the basic tenets of early-20th-century Modernism. As a design conceived on paper and executed with computers, Meadow House 1 spans an arc of my life from visual design, away and then back.

See a complete gallery here: www.jordanorlando.com/mh

Wednesday, August 24th, 2016

•

Politics

I just realized that David Brooks (“Why America’s Leadership Fails”) is like a pre-Copernican (with the Post-Structuralists and Marxists*, or, really, any reasonably decent social critic, as Copernicus): He’s constantly tying himself in knots trying to make the world fit into an obsolete, ill-informed pattern he won’t let go of.

Hillary Clinton has to be bad, and (from yesterday’s example) Romney has to be good, because that’s how things work—if you completely ignore fifty years of social progress and political and social change (which, in turn, worked as a culmination of 19th century post-industrial and 1920s-1930s enfranchisement/social justice movements).

Hillary Clinton couldn’t exist in the minds of John Birch or Milton Friedman or Leo Strauss, because she couldn’t exist in the societies they knew; the progressive transformation that made her possible hadn’t happened yet (just like the capitalist rot of offshoring and banking that made Mitt Romney possible didn’t exist either). So, Brooks can’t see them, any more than other astronomers could see the heliocentric model…he just sees “rich businessman good; strident woman bad” and runs in tight little circles elaborating.

You’d expect this on the porch of an old-time Kansas general store (or, maybe in that town’s library), not at The New York Times. But such are sinecures.

(Commentary grew out of Yastreblyansky’s excellent discussion here—Yastreblyanskyis one of the most consistently brilliant political/critical voices I’ve ever read. In a just world, the legitimately erudite and perceptive Yastreblyansky would have the NYT real estate and David Brooks would be a single-digit-readership crank on a Blogger page.)

*Yastreblyansky refers to Adorno and Marcuse.

I’ve been reminded that I used the Coopernican metaphor before.