Wednesday, February 8th, 2012

•

Comics

If you want to actually see and hear Alan Moore discussing his work and other topics (which is not easy to do), Here’s a two hour chat with Moore (who’s lurking in some Alan Moore steampunk castle somewhere in foggy, soggy England, hunched close to the camera with a light shining upwards on his face, exactly as you’d expect). The occasion is a fundraiser for a project to raise a statue of late comics author Harvey Pekar (he of the legendary R. Crumb collaborations), the Raymond Carver of comics, in Cleveland (which I think is a great idea). I have to thank Hamza Walker for introducing me to the work of the brilliant Pekar, back in Chicago, years ago (and I also have to thank Lauren Tillinghast for introducing me to Alan Moore’s work at about the same time). In the clip, Moore talks about Flatland, quantum theory, “theft” of 19th century literary characters, magic, “live Chinese Elvis” and much more. Two hours of Moore drinking black tea and holding forth…not for the meek.

Tuesday, February 7th, 2012

•

Design

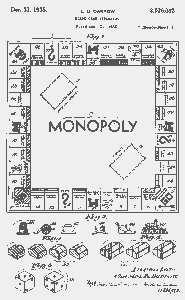

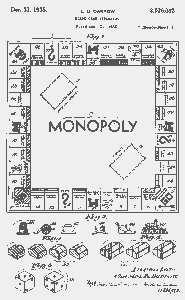

The cover page of Charles Darrow’s 1935 patent application for the Monopoly game. Apparently the origins of the game are in dispute—the game was invented years before Darrow’s Atlantic City version (and the game’s concept has straddled the edges of intellectual property definitions since its creation). The original version of the game had an entire second stage of play in which all the real estate monopolies are dissolved—for various reasons this concept doesn’t survive into the current incarnation of the game.

But the visuals do! My grandfather owned several automotive patents, so I’m familiar with the rigid, inflexible visual lexicon of patent applications (of which he, my grandfather, was very scornful—he hated to have to draw his streamlined compound curves in a style created in the horse-and-buggy era). Patents are still drawn in the same archaic crosshatched style today as they were at the turn of the century. But the “Monopoly” patent is interesting (especially in light of the dubious origins of the game) since it looks more like a design trademark or copyright application than a patent diagram. Look at that game board image, and how nearly identical it is to the contemporary version of the game! Darrow is implicitly asserting that the game must be played this way, from a visual standpoint, on a board that looks like this. The abstractions of “Monopoly” are fused to the game’s fonts, images, typography and proportions. (By contrast, Apple’s iPhone/iPad patents abstract the geometry of the machines to a much greater degree.) If you don’t use Futura Light, it’s not Monopoly.

Sunday, February 5th, 2012

•

Movies

Of course we all remember John McTiernan’s strangely Pirandellesque 1993 Schwarzenegger vehicle Last Action Hero, and how that movie shows two worlds; a “movie world” and a “real world” (and how, of course, they’re both “movie worlds” is a strict sense). There’s exactly the same contrast going on between two Fincher movies: Se7en and Zodiac. Both are “serial killer movies,” but they couldn’t be more different beyond that (aside from both being so profoundly Fincher-esque). Look at the serial killer hunt in both movies: In Se7en it only takes a week, and involves chases and shootouts, and is very lurid, and it’s the big character moment for both cops (one “about to retire,” which is as cop-movie as it gets; one getting his wife’s head delivered to him in a box, which is admittedly more unusual), and the killer is some kind of crazy genius who wants to get caught and has this huge social message for all of us. In Zodiac, decades go by, and everyone just gets older and tireder, and they never catch anyone, and the murders are pointless and tragic, and nobody runs or waves a gun, and the cops have to spend all their time leafing through filing cabinets and dealing with jurisdictional and procedural hurdles (while their hair turns gray over the years), and marriages fall apart (not through decapitation but other ways) and the prime suspect isn’t a diabolical mad genius; he’s just a fat guy with a record for child molestation and a string of bum jobs. (And the cryptographic messages aren’t decoded by the chisled, toughened homicide detectives; they’re decoded by skinny guys in labs with pocket protectors.)

If they had been made in the reverse order, would they have been as successful? Of course not, and not because of the public/critical awareness of the development of a director’s “vision” either; it’s just that, in 1995, the audience wouldn’t have accepted a three-hour procedural (inspired, as Fincher notes, by All The President’s Men), and, today, Se7en would probably blend in with the slew of movies it’s directly inspired and be regarded as a passable (if wildly implausible) thriller. It’s great to see the art form actually maturing in this way (or, becoming more “realistic,” whatever that means), after living through so many retrograde periods like the mid- to late-1980s in which so many tremendous artistic cinematic breakthroughs were summarily dismissed.