Wednesday, April 25th, 2012

•

Writing

This is the M. Night Shayamalan film in which people’s heads are falling off. You see people sitting around on park benches, in offices, driving etc. and their heads fall off. Pause and then a spurt of blood etc; they fall over. More people’s heads fall off.

M. NIGHT SHYAMALAN (dressed as priest): “My entire point of view is based on the church but that is going to have to change.”

RYAN REYNOLDS (stunned, haunted tone): “People’s heads are falling off”

Cut to small suburban home where mother is having to make do on her own with three errant kids because her husband’s head fell off. (Note: her husband is NOT Ryan Reynolds; this is somebody else entirely.)

KIDS: “Mom! What are we going to do?”

AMY ADAMS: “I don’t know dear.”

KIDS: “But what if YOUR head falls off?”

AMY ADAMS (reassuring): “Then you’re just going to have to make do on your own, as I have always taught you. Remember your father.”

KIDS: “Okay.”

Meanwhile in Philadelphia more people’s heads are falling off. Scientists are no closer to an answer; the National Guard has to be brought in, but their efforts are waylaid due to soldiers’ heads falling off. Telescopes are pointed at space, but no answer is forthcoming. Cut to Ryan Reynolds (dressed as a doctor) talking to Amy Adams in the parking lot.

RYAN REYNOLDS (stunned, haunted tone): “I’m sorry I was too late to save your husband”

AMY ADAMS: “That’s all right.”

KIDS (in back of SUV): “MOM!”

Finally scientists are beginning to develop a theory: all those people whose heads fell off seem to have something in common, having to do with a trip on a cruise ship that they all took last year. It appears that there is something out there, in the ocean; the scientists are looking at big charts of the North Atlantic.

M. NIGHT SHYAMALAN (dressed as priest): “Does this have anything to do with the Titanic?”

LEAD SCIENTIST: (hits him)

Then Ryan Reynold’s head falls off, but not before he discovers THE ANSWER. Cut to Amy Adams in SUV with more kids.

AMY ADAMS: “We’re going to have to handle things on our own now.”

KIDS: “MOM!”

Then the husband comes back. It turns out he wasn’t on that cruise ship after all; he was having an affair but he feels really bad about it. I don’t know what happens next but I just looked at my watch and there isn’t much more of this. Crane shot of a lot of cars stalled on the highway leading out of Philadelphia; music swells. I wish I knew how it ended, because there’s probably another twist coming.

Wednesday, April 11th, 2012

•

Movies / Politics / Writing

Not “trailers” as in “Coming Attractions” (or, the three-minute-no-second ads for movies that are a burgeoning art form in themselves) (I made one myself for my favorite movie). I’m talking about actual trailers, or “mobile homes” or “ten-wides” or “single-wides” depending on what sort of construction or zoning nomenclature you’re using.

Would you ever want to live in a trailer? Okay, no, would be the immediate, obvious answer, unless you had to. But a surprising, statistically-disproportionate number of movie characters do exactly that, and they’re not necessarily characters who are down on their luck. Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) not only cheerfully abides in what appears to be a standard ten-wide (above) in both Lethal Weapon and Lethal Weapon 2 (wherein it’s destroyed by machine gun fire from a helicopter) but genuinely enjoys it (“I like living the way I live!”), even managing to bring ersatz-South-African hottie Patsy Kensit there for the kind of Olympian first-date sex marathon that occurs so often in ‘Eighties movies. Bud (Michael Madsen), Bill’s beloved (and doomed) brother in Tarantino’s operatic Kill Bill saga, occupies a trailer that’s somehow even more majestic and romantic (especially as photographed by Robert Richardson); Uma Thurman and Daryl Hannah engage in the epic’s fiercest battle (which is saying a great deal) within its twelve-foot-wide, flakeboard-paneled, shag-carpeted confines.

Natalie Portman’s also a trailer-dweller in Thor (the thunder-god’s appearance there embarasses her far more than is warranted; after Asgard, all mortal dwellings must look about the same). David Lynch created a spellbinding neo-Lovecraftian surrealist tableau (“LET’S ROCK” painted in soap on a Chrysler windshield) within a twilit trailer park in his underrated Twin Peaks Fire Walk With Me (Harry Dean Stanton was the memorable custodian for whom the murders meant “just more shit I’ve got to do”). I think I remember Sam Shepard bringing the drama within the laminated walls of trailers more than once, and I think Jodie Foster’s Oscar™-winning turn in The Accused had her talking across her trailer’s formica table. Mickey Rourke’s home in The Wrestler is the only recent movie trailer I can think of that’s meant to convey pure pathos and defeat, unleavened by iconoclasm, hope or Robert Ventura-style “tin pan alley” tinsel-romance. I’d be happy to be reminded of other movie trailers I’m forgetting.

The Wikipedia “trailer-park” entry is heavily politicized: obviously the demographic referred to as “trailer trash”—the 6.8 million Americans (2.1% of the population; nearly as many as occupy all five New York City boroughs) who live in “mobile homes”—does not appreciate the appellation and are, like Orwell’s London “proles,” on the correct side of the economic battle lines; they are warriors in our army and no other (unless one counts “God’s army,” which, unfortunately, one must). The life lived within pre-painted aluminum panels atop a cast-concrete frame, suspended over the ghosts of automotive axles, is obviously as rich and deep an American odyssey as any other. I don’t think I’ve ever even seen the inside of a classic trailer home; my insular ignorance needs to be corrected.

ON EDIT: I forgot all the trailer sequences in No Country For Old Men (photographed with burnished Fredrick Remington Chiaroscuro by Roger Deakins). I’m not counting the “industrial” trailer complex where Joe Pesci and Sharon Stone seal their fates in Casino.

ON EDIT II: Of course all movie stars, regardless of the tax bracket their characters occupy, rightly regard their own on-set trailers as the most coveted, jealously-guarded, envied, irreproducible real estate around; the irony was not lost on me when I made this post. You’ve got to be an internationally-famous multimillionaire to bed down in one of those ten-wides.

Monday, March 26th, 2012

•

Movies / Politics

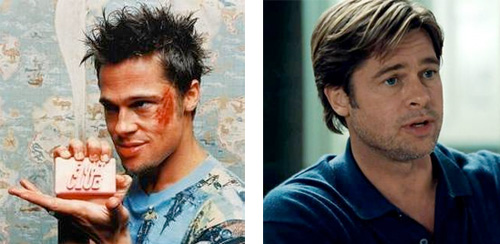

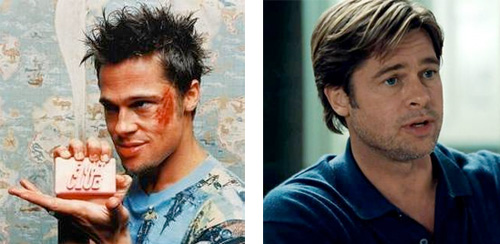

After finally watching Moneyball I realized what it’s got in common with David Fincher’s sublime, belatedly-appreciated tract Fight Club: Brad Pitt as an onscreen salesman for an abstract idea. In both movies, a reasonably subtle concept (that runs strongly against the cultural grain) has to be conveyed clearly to the audience, not as some ancillary grace note, but as the fundamental armature of the story.

Chuck Palahniuk’s urgent anti-consumerist (near-Marxist) diatribe and Billy Beane’s (somewhat less revolutionary—not literally about blowing things up, as in Fincher’s pre-9/11 epic) statistical baseball-team assembly methodology (which contains a much larger idea about the proving grounds that surround entrenched social systems) are each densely-packed, abstract constructions. And yet, in each movie, Brad Pitt makes speech after speech, hammering the idea until even the most resistant onscreen listeners (and audience members) not only get the point but passionately agree.

It turns out that our generation’s Redford has a much more clearly defined talent for delivering rhetoric (in the classical sense) than his activist predecessor (whose ’70s movies worked just as hard to advance then-current anti-establishment agendas). Brad Pitt is our big-screen TED-talk lecturer (maybe he can be paid to deliver physics lectures or literary analyses). Who would have guessed, back when he was showing Geena Davis how to rob a convenience store?