Friday, June 15th, 2012

•

Writing

On my desk in front of me is a receipt from Supreme Hardware on West 73rd Street from 10:30 this morning for $8, which I spent on a 1/4″ masonry drillbit that I used to mount bookshelves in my apartment. The new shelves, which I finished today, let me finally put away an enormous stack of unorganized books that had accumulated on my living room floor near my reading chair. While sorting these books I found many I hadn’t seen in years, including a damaged paperback Lytton Strachey biography that I bought off a blanket on the street; a page was marked with a folded and faded receipt which, unlike today’s strip of paper tape-ribbon, from the hardware store’s old-school register, is a full digital transaction record.

Apparently I was at a Krispy Kreme at 285 West 23rd Street at ten minutes to two on the afternoon of June 20th, 1998, where I bought a large iced coffee from somebody named Lonnie. What was I doing on West 23rd Street that Saturday afternoon? (Google provided the day of the week.) Is there still a Krispy Kreme there? Was I alone? Who was Lonnie? (Male or female?) Was I carrying the Lytton Strachey book with me or did I absently stick the receipt in my wallet and then pull it out later when I needed a bookmark? I remember that I got mildly interested in Strachey after I saw the Stephen Frears movie called Carrington (with Emma Thompson as Dora Carrington and Jonathan Pryce as Strachey); IMDB tells me that the movie came out in 1995, which corresponds to my memory, because I saw the movie with a friend who worked at a website (an “internet company”) for which I was doing some work at that time. The movie was in theaters for a few weeks, and I could probably figure out where I saw it (but not when); I might even have a ticket stub or a receipt from the restaurant where we had dinner after the movie.

But none of this helps me figure out what I was doing on that Saturday afternoon, three years after that; whether I was reading the book then, or later that day, or the next day, and what made me go into that Krispy Kreme and buy that large iced coffee that I don’t remember drinking from Lonnie, a man or woman whom I can’t picture and who, if he or she is still alive, may only have the vaguest memories of working at a Krispy Kreme in Manhattan fourteen years ago and certainly has no memory at all of me and my iced coffee. But it happened that day, and at exactly 1:51 PM I handed a twenty dollar bill to Lonnie and got $18.11 back and left the Krispy Kreme with my large iced coffee, and the receipt went into my pocket and then into the book and I never saw it again until today. What did I do with the rest of that day? Who was Lonnie? The thermal ink on the receipt has faded to near-invisibility; I can barely see the 8-bit characters that reveal just one incidental forgotten moment of millions, billions in this city every day, every decade, every century.

Monday, June 11th, 2012

•

Movies

What do Benjamin Braddock, Gordon Gekko and Don Draper have in common (beyond the obvious strained comparison)? The alliterative naming isn’t always a writer’s deliberate stab at mythmaking, but it’s a self-conscious maneuver that draws attention to the character’s archetypal characteristics by leveraging your mnemonic systems, forcing you to memorize the name even if you don’t want to (just ask Superman, whose past and present unrequited love interests and mortal enemy all come with double-L brands).

Braddock, The Graduate‘s title role, was famously miscast (the protagonist of Charles Webb’s novel is a Redford type, and Redford was nearly cast before a famous verbal exchange with Mike Nichols* shut him out of the role)—Dustin Hoffman was ten years too old and physically wrong for the athletic letterman/scholar character but his distillation of his generation’s famously opaque confusion (the most important conversation in the movie—the moment when he connects with Elaine—is inaudible) was a compelling Rorschach blot for people just a little too old to scream for the Beatles.

Gekko and Draper are each “throwbacks,” but in different ways: Gekko was cut from the thick nostalgic cloth of Reagan-era yearning for the lost glories of a pre-New-Deal robber-baron epoch, although his forceful counter-reformation against regulation, forbearance and (really) common decency was coated in 1980s irony (just remember his self-effacing grimace to future “winner” Charlie Sheen after his “Greed is Good” speech). He know’s he’s perpetually onstage (even when the proscenium is just Oliver Stone’s gold-burnished widescreen Panavision frame).

As retro-emotion-magnets go, Don Draper has the advantage of actually being from the past (from Braddock’s era, actually), although it’s obviously an invented, synthesized past meant to comment on the present and the intervening decades, distilling the lessons of Braddock’s and Gekko’s America through the lens of post-iTunes/DVDs, post-Sopranos long-form “episodic televised cinema” (or whatever we’re supposed to call this burgeoning new art form that works like television but breaks down into seasons rather than episodes as discrete storytelling blocks). Draper’s easily the deepest of the three characters; when he makes his big pitches, we can hear them (and they’re significantly more sophisticated and existential than Gekko’s one-note pep talks—in this longer, more detailed storytelling format, Gekko’s embryonic acquisitive appetites have mellowed into a sadder, more profound yearning in the John Cheever mode that nonetheless remains as grimly insistent as it was twenty-five years ago).

It’s a completed syllogism: Draper aims Gekko’s argument straight back at Braddock, crossing the decades to insist that the generation “On the Barricades” re-locate their marbles (or, at least, just reach for their wallets). Some grandiose impulse makes a writer bang the same key twice when naming a protagonist; in these three cases, the inflated, iconic ambitions were fulfilled.

* Nichols asked Redford if he’d ever been rejected. Redford replied, “Define ‘rejected.'” Re-telling the anecdote, Nichols basically explained that that was it—there was just no way that Redford could get into the character of Braddock.

Thursday, May 31st, 2012

•

Design

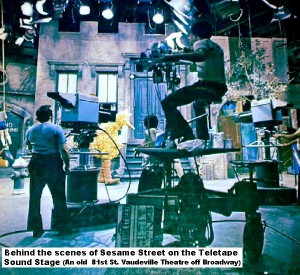

My father worked for Children’s Television Workshop intermittently through the 1970s, starting as a public relations consultant and as the speechwriter for Joan Ganz Cooney, the founder of CTW and, essentially, the creator of Sesame Street. He was involved in the earliest stages of the show’s inception and evolution in 1969-1970, when the idea of publicly-funded programming for children that was firmly grounded in academic principles of pre-school education (as well as a sociological and political/economic understanding of the needs of modern children, particularly in inner cities, where television often took the place of parenting or schooling) was brand new. Dad worked closely with Cooney and others to develop the presentational materials that were used to draw attention to the project and even attended the White House Conference on Children and Youth in 1970. Sesame Street was very much a product of the social upheavals of the late ’Sixties, and its ideas and methodology (including the Marshall McLuhan-esque concept of creating “commercials” for the numerals and letters of the alphabet which “sponsored” the show), while commonplace today, were groundbreaking and revolutionary at the time. Also, not least, Sesame Street introduced the world to Jim Henson’s Muppets (which, to Joan Cooney’s decades-long chagrin, could at one time have been bought outright by CTW but were not).

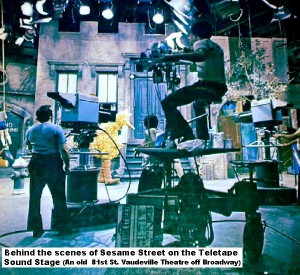

Sesame Street was, at that time, videotaped at a facility called “Reeves Teletape Studio” on Broadway and 81st street, within an old, reconverted vaudville theater. (The building was later demolished, but its façade was retained by the developers and still stands; today, the location is a condominium fronted by a Staples and a Starbucks.) By the 1980s, the program had moved elsewhere (and is now taped at Astoria Studios in Queens), but the original, 1970 “street” that was viewed in homes and classrooms all over the country was really a large stage-set behind a blank marquee on the Upper West Side.

The original "Keith's" Vaudville Theater (which became Reeves Teletape); Broadway and 81st

The same location today

In 1971 or 1972 my father brought me to Sesame Street to see the set and meet the cast. It was, to say the least, an unforgettable experience. I still vividly remember our first arrival there, on a rainy day, heading east on 81st street to the grimy, windowless side-door (the vaudville theater’s original exit) which was opened from the inside (by some mysterious pre-arranged signal) and gave on a dark corridor of black-velvet draperies that led to a brilliantly-lit space where I saw something that blew my mind for good. I had been expecting to visit a street (the actual, fictitious place I imagined that I was seeing on our black-and-white television), but, instead, I was inside an cavernous, floodlit room where the vividly-colored buildings had been (apparently) re-built at an arbitrary angle and surrounded by painted backdrops and dozens of pieces of theatrical equipment. I was allowed to wander around the set for a long time, looking up-close at the wooden construction, the painted sidewalk, the fake plastic trees, and at some point it fully sank in that this was Sesame Street—that the imaginary, sunlit stretch of Harlem I was so familiar with was where I was standing at that moment. I went back several more times, but I think that first visit was one of the most important moments of my childhood; an entire raft of cinematic and architectural ambitions and obsessions (which still burden me now) were ignited on that day.

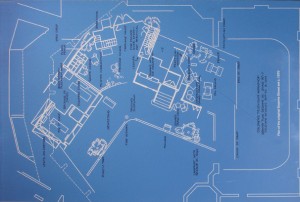

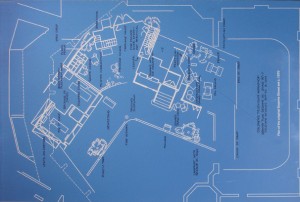

In April 2006 I visited the New York State Museum in Albany (with my friend Brendan Kennedy and his daughter Annabella), where the original 1970 “123 Sesame Street” building façade is on exhibit, along with a display panel depicting a reproduction of one of the original construction blueprint floor plans. At that time, I was just beginning to teach myself digital CGI modeling and rendering (I had not yet done my animated “Buehrig Design” film for the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum’s gallery of my grandfather Gordon M. Buehrig’s revolutionary car-design methods) and the Sesame Street façade and plan (which I photographed exhaustively on that day) were the basis for my first large-scaled CGI project (in Autodesk Maya), a full reconstruction of the original Sesame Street set.

The 1970 floor plan blueprint (from a photograph taken at Albany's Museum of the State of New York; parallax removed in Photoshop)

Othographic plan view of my completed digital model

Six years later, after many stops and starts and intervening books and other projects, the original “labor of love” is complete. Ultimately the task included steep learning curves in many aspects of digital modeling (including diving into the deep waters of “nCloth,” Maya’s system for controlling dynamics that causes the canvas awnings to droop and wrinkle properly). Looking at renders of the completed model, I’m transported back to that day in the early ’Seventies when I was just another child walking across that painted sidewalk under the bright stage lights, gazing up at the false-front buildings and at the bright canary feathers on Big Bird, eyes wide open. In retrospect (and my father has always asserted this) the Harlem “inner-city” locale—with stealth-educational “graffiti” that showed letters and numbers—was a 1970s-utopian cultural conceit (since most viewers of the show were actually well-to-do white kids), and, over time, the street’s grime and disrepair have been downplayed, so that the current iteration is vastly cleaner and nicer…but, for me, that original, filthy-looking stage set is the “real,” eternal Sesame Street. My father has long since moved on to other things, and Sesame Street has become a worldwide cultural icon (and the precise geographical spot where “Hooper’s Store” stood is now behind the barista counter at a Starbucks), but, at that time, it was a magical Upper West Side destination on a little kid’s rainy afternoon, and I’ll never forget that.

Click here to see more images of my Sesame Street model.