Friday, November 9th, 2012

•

Politics

If only one good thing comes out of the rhetorical cacophony surrounding this year’s election results, I hope it’s this: can we please, as a nation and as a society, reverse the inverted positions of “provider” and “taker” in our political language?

Former Nixon economic adviser Herb Stein first used the term “supply side” in 1976, well before Reagan-era demagoguery fueled the “Laffer curve” and “trickle-down” economics of the 1980s—the exact policies that are, astoundingly, still being “debated” decades later, long after repeated disastrous experiments in non-proportional taxation and infrastructure starvation have demonstrated conclusively how fraudulent and fantastical these non-Keynesian theories really are.

But beyond the overwhelming evidence (multiple collapses, joblessness, a lost manufacturing base, and income disparity graphs that look like breeder-reactor chain reactions), the entire premise needs to be challenged on a more atomic level. The basic armature of this half-century-long exercise in graft and deception is (as with most things) visible in the language itself: what does “supply side” mean? Why is every Red State poster and Drudge Report reader (as well as Rush Limbaugh and other prominent conservative luminaries) so convinced that President Obama’s supporters are “the takers?” How did the basic facts of capitalism get so reversed?

Wealth is created by workers; by wage-earners, by laborers. Just as happened in pre-mercantile economies, farming, industry (of any kind), trade and sustenance for any community of any size is based on the generation of wealth through labor. Starbucks cannot earn a dollar without somebody standing behind a counter creating a latté from beans that were picked and paper cups that were manufactured on assembly lines by machines that were operated by line workers and designed and constructed by engineers who were trained by teachers; a chain of labor that turns the raw stuff of the earth into the elements of our modern lives.

Yes, entrepreneurs “create” businesses. Yes, they “innovate” beyond the constraints that limit the work product of most employees—but they require capital to do it. Either they have investors, or they are independently of means, but in either case their venture capital is invariably siphoned from the fruits of somebody else’s labor. And yes, they work hard—although I doubt that their “hard work” compares in any meaningful way to that done by what we used to call “blue-collar” employees, none of whom have chefs or private jets or European vacations or limitless medical care and young retirement ages to compensate for their toils.

In fact, when I look at the “management class” (or “ownership class”)—those of the notorious “1%” who actually deign to work at all, rather than sitting on dividends or inheritances—I don’t see meaningful “production” of anything. And, at least people like Sam Walton are causally responsible for the creation of businesses; today’s most strident and vocal top-earners tend to be Wall Street types, whose wealth is completely disassociated from the creation of any goods and services at all (and whose predatory activities strip ailing companies of their employees and assets in order to enrich their own bank balances).

Has Mitt Romney (or his guests at that fundraising dinner where the clandestine “47%” video was captured) ever done a meaningful day’s work in his life? Does he do anything for his obscenely high Bain Capital salary? (Remember the controversy about the two-year period during which he was “uninvolved” but still drawing a paycheck.) Not only is Romney sitting on a massive family fortune (like Donald Trump and so many others who lecture us about the value of “hard work”), but his “company” has literally destroyed the value of dozens of other American businesses, liquidating and absorbing their assets in exactly the way that Reagan-era movie icon Gordon Gekko famously defended. Was Gordon Gekko a “provider”?

This basic inversion of the language of commerce and business must be turned the right way up. Once the Roger Sterlings of the world are properly labeled as “takers”—once having one’s “name in the lobby” is understood to be a result of extraordinary good luck (genetic or otherwise), and, far more often than not, license to “rest and vest,” rather than a badge of personal achievement—and the tireless line-workers and employees and wage earners are properly regarded as “makers,” then we can begin to have a reasonable conversation about American economic strength and recovery.

Monday, November 5th, 2012

•

Writing

In 1965, during the planning stages of Star Trek, creator Gene Roddenberry was concerned about how to portray planetary exploration on his new show—not because of the (projected) limited resources of space travel, but because of the (very real) limited resources of television. Would Roddenberry’s spacefarers actually need to land their “Starship Enterprise” every week? The objections were irrefutable, from a TV-production standpoint: it takes too long; it’s too complicated…and the story can’t get moving until ten minutes into the episode (after a laborious “landing” sequence). Plus it’s expensive; creating footage of all that landing and taking off (the way Roddenberry was probably picturing it back then: something akin to the post-George-Pal effects in Forbidden Planet or When Worlds Collide), given the primitive production values and the tiny budget of the show, would be impossibly expensive.

So, in a stroke of genius, he invented the “transporter,” the famous machine that instantly moves characters from place to place as arbitrarily as a magic spell. This is the only reason “Beam me up, Scotty” exists: to expedite and cheapen (literally) the TV storytelling. “Energize!” shouts Captain Kirk, and (with a lap dissolve, superimposed backlit glitter and a sound effect) he and all other relevant characters are immediately placed directly into the story—it’s a deus ex machina in reverse. (Later, the proto-cellphone “communicator”—and its indispensability with regard to “locking on” to a transportee’s “signal”—was invented purely because the transporter made it correspondingly too easy to get out of the story—with Kirk’s communicator stolen or disabled, he’s trapped in place and can’t run away from the plot; he’s got to solve the problem himself.)

Note that that “transporter” has nothing to do with reality; like the “warp drive” (which facilitates faster-than-light travel) it’s a completely fanciful conceit; an invention that belies the emphasis Roddenberry was placing on realism and believability for the simple reason that, without this miraculous “technology,” there could be no Star Trek. Arthur C. Clarke had already decreed that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic;” Gene Roddenberry effectively took him at his word.

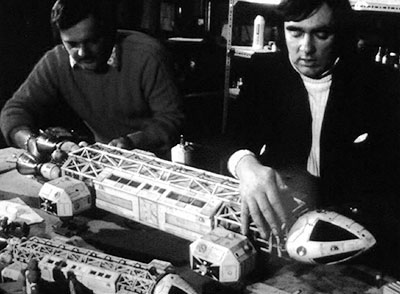

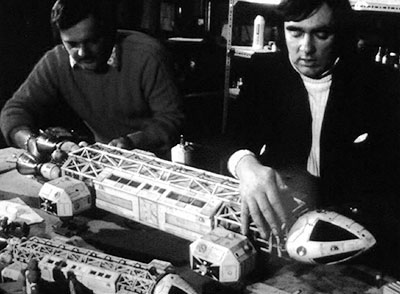

Flash forward ten years and Gerry Anderson is creating Space: 1999. The post-moon-landing, post-Kubrick ethos of his new show is clear: absolute realism. No transporters; no “warp drive”—only “real world” technology based on the NASA missions that have by now already taken place. (The historical immediacy is right in the show’s title.) Instead of magical technology, Anderson would have “Eagles” (Apollo reference duly noted): meticulously-designed, sturdy, multipurpose transport craft (see images above). “Moonbase Alpha” would have an entire fleet of them, and a crew of pilots, techs etc. All very realistic: NASA-style pipe superstructures; visible jets from the engines; space suits with air tanks and fishbowl helmets; shock absorbers that bounce during landings; big tanks of fuel; special landing platforms; complicated instrument panels surrounding the two pilots as in an old Gemini capsule; hulls covered with metal sheeting and protruding rocket-engine jets and grime and utilitarian paint schemes (yellow-and-black “caution” stripes etc.).

From a TV production standpoint, it’s fantastic-looking, because Anderson had one of the highest budgets ever given to a British syndicated TV show (and had already developed a mature, sophisticated approach to practical SFX using miniatures during his Thunderbirds puppet-show days). So Brian Johnson, Nick Allder and Martin Bower (who would go on to win Oscars for Alien and The Empire Strikes Back) could create amazing shots of detailed models with real compressed-air engine jets and of the Eagles flying with the “astronauts” visible in the windows. They quickly amassed a “library” of Eagle shots: takeoffs, landings, orbital approaches, banking turns etc. that they could use any time “for free.” And of course, the “interior” elements of Eagle flights are just more studio set shots: Dressing up actors in those realistic spacesuits and filming them in the Eagle cockpit set cost the same as filming the same actors standing around inside the Moonbase.

But the result of all this is a wild imbalance in the storytelling. Remember that Roddenberry was trying to save time and money—but by coming up with the “transporter” he invented what’s presumably a cost-effective technology within the narrative; the Enterprise can refuel and restock its provisions, and anyway the “transporter” (we are repeatedly told) simply drains “energy” from the main “dilithium-powered” engines and the (appropriately) mysterious 23rd Century power train they depend on. So beaming people up and down over and over (as happens during any normal episode) makes sense.

However Moonbase Alpha has severely limited resources (and much is made of this every episode). They can’t refuel or restock; if they lose any of their personnel or resources (including the precious fleet of Eagles) there’s no way to get any of it back. (And, a 52-minute “hour” of television hadn’t gotten any longer.) In this context, launching an Eagle would be an incredibly risky and expensive last resort—like activating a fuel cell or turning on the cabin heat inside the Apollo 13.

But it happens constantly. The Moonbase inhabitants keep flying the Eagles back and forth, over and over. John Koenig, their “Commander” (Martin Landau) will launch Eagles at the slightest provocation, and then send more Eagles after them to intercept them, bring them back, dock with them, shoot them down. Eagles crash on the lunar surface (very gently, so as not to damage the expensive models), they blow up; they’re crushed by gravitational forces and by interstellar “anemones;” they tumble off into space. And Koenig launches more Eagles, in long montage sequences of launch pad model shots and “astronauts” running down corridors and pilots in cockpits reciting NASA-style launch jargon. Because nothing’s actually happening; it’s just library footage and a few practical model shots unique to the episode (without optical effects) and actors elsewhere on the same stage pretending to stare through cockpit windows that don’t even exist. (All the Eagle interiors are the same set, which has no front.) It’s more expensive to show Starsky and Hutch driving somewhere; you’ve got to go on location with a car. On Space: 1999 it’s just a different room and another trip to the film library. The result of all Gerry Anderson’s innovations is an incredible waste of time (real and imagined) and fictional resources in every episode, although the net costs for the filmmakers are the same (and nobody is asked to believe in a “transporter”).

So the price of “realism” is less realism. The whole phenomenon reveals the strange psychological balance of science fiction and fantasy: it doesn’t matter how little actual sense the premises (or their execution) make. It only matters how real it seems, and in this case it’s less a question of physics and economics than of the right number of pipes and wires and metallic sound effects and flashing lights and complex verbal jargon—and the correct balance of scenes and confrontations and dramatic suspense through the four acts of an hour-long television drama. Just as The Godfather‘s documentary-style photography and subtitles and faux-historicism create the impression of journalistic reality (although the novel’s and movie’s portrait of mafia crime ranges from outlandishly misleading to fantastical) and John le Carré’s shabby, threadbare, ideologically-tortured MI6 is really no more accurate than Ian Flemming’s version, science fiction and fantasy traffic in a more intense version of the same conjuring trick, by which “believability” appears to emerge through narrative/representative logic but really operates like dreams—the sensual feel of an imaginary environment, its consistency and recognizable fabric, inspires acceptance and belief in a way that no waking logic can undo.

Wednesday, August 1st, 2012

•

Writing

So “The Beatles” (a business entity consisting of Sir Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, Olivia Harrison, George Martin, George Martin’s son Giles Martin* and a raft of attorneys and corporate infrastructure) have released a “new” digital-only album called “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which is a collection of fourteen tracks from the Beatles’ back catalog. All the songs are from what I think of as the “astronomical main sequence” except for the “Naked” version of “I’ve Got a Feeling” (a near-identical adjacent take) and the “Anthology” version of “The End” (which, unlike the “Abbey Road” version, lets you hear the beginning of the song, wherein the Beatles take 16 bars to build up that indelibly ferocious momentum that George Martin’s perfect splice from “Golden Slumbers” air-drops us into as deftly as Daniel Craig landing inside an exploding train and adjusting his cufflink).

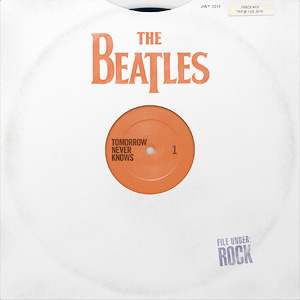

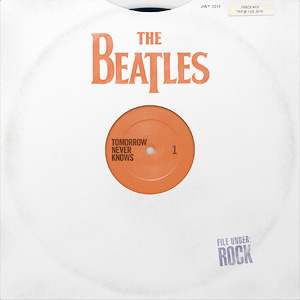

What is this “album”? Can we even call it an “album,” or is it ontologically indistinguishable from a “tracklist”? I, myself, put “Tomorrow Never Knows” together in iTunes in about ten minutes, for free. But, when I listened to it, it nonetheless felt like listening to a record, as intended: the exquisite album art (the only expenditure in the entire release) seems designed to force this interpretation with its aggressively retro “battered vinyl sleeve” design, complete with ersatz dirt and false rubber stamps (“FILE UNDER: ROCK”) and handwritten labels. (It’s even faker than the “handwriting” on The Who’s fake-bootleg “Live at Leeds”: this release not only won’t be pressed onto vinyl but won’t even exist as a compact disc or in any physical form at all; it’s an intellectual abstraction coupled with a pretty picture.) The new “release” is (as has been pointed out elsewhere) formally similar to “Love Songs,” the “red album,” the “blue album” and several other Capitol/EMI compilation records (actual vinyl records) released in the 1970s and 1980s, back when the Beatles were more recent than Nirvana is now. But in those days, before Walkmans, before iTunes, before portable Mp3 players, those discs were necessary; they were the best way for my generation to discover the band. Why, in this era of bittorrent and YouTube fair-use-exploiting videos and traded hard drives with hundreds of overcompressed songs, does this work? Why is this “album” charting in England? Why are we rewarding the remains of “Apple Corps” with more money?

Because it sounds so good. Some obsolete element in my lizard brain sees the circular window in the fictional “sleeve” revealing the fictional “label” with the little hole and conjures up an imaginary turntable and an imaginary tonearm and even a point where the record must be turned over (right before “Back In The U.S.S.R.”) and I’m sold. It’s better than the countless Beatles tracklists I’ve made myself simply because it’s official: because it was assembled by George Martin (or his son, or somebody endorsed by him) rather than a mid-Seventies Capitol Records AOR-executive; because it’s a spectacular set, a mix tape made by the band itself; because the songs, after all this time and all those thousands of listens and the decades it took me to memorize every note, just need to be tweaked into a clever new order to become as fresh and vital as whatever Thom Yorke and Nigel Godrich have on their laptops. It’s not even chemistry; it’s alchemy—the elements do not re-bond into new compounds; they remain exactly as they were, but the ancient magic, the rhythms Aristotle believed would rattle the foundations of the Polis, are re-generated into gold one more time. It’s no accident that the title track is the notorious nonlinear experiment (called “Phase 1” when it inaugurated the “Revolver” sessions) for which AMC paid a quarter of a million dollars in order to allow Don Draper’s moddish wife to persuade him to listen to on Mad Men, and then impatiently turn off, only to have the track return like the molten Terminator—or the finger-blistering end of “Helter Skelter” (also included here) which fades back in for its zombie-like stagger to the finish line. Don Draper can’t stop the Beatles in AMC’s artifically-reconstituted 2012 simulacrum of 1966 and neither can anyone else.

ADDENDUM: Rehabilitating not one but two of the “throwaway” contractual-obligation tracks from “Yellow Submarine” (Harrison’s “Only a Northern Song” uses “contractual obligation” as its subject matter) is cheeky, unabashed brilliance. Even Tim Riley grudgingly laments the Beatles’ late-1967 creative slump (the calm before the “White Album” storm), but “Hey Bulldog” and “It’s All Too Much” are so flattered by this fresh presentation that I have trouble believing they’re still the same tracks I’m familiar with.

*Giles Martin is the man responsible for digitizing the entire canon of 4-track and 8-track recordings (not the cleaned-and-reconverted stereo and mono mixdowns released two years ago but the original multitrack studio masters), producing The Beatles Love Cirque Du Soleil mashup collection as a side-effect of that archival procedure—essentially, disassembling and recombining the songs’ elements into new crystal-pattern alignments; a “Goldberg Variations” alternative to the main compositional library.