Wednesday, March 6th, 2013

•

Movies

Since the Oscars there have been dozens of articles I’ve noticed links to, and some I’ve skimmed or read, in different kinds of publications, about how “everyone” (or “EVERY WOMAN ON THE INTERNET”) can’t stand Anne Hathaway, and I haven’t been able to make heads or tails of it. (See The New York Times, Huffington Post, Slate, The Daily Beast, Express, CNN, and Salon for just a few of the elaborate theories.) Usually, offscreen shortcomings of movie stars don’t really affect my judgment of their work (or, more important, of their onscreen personae, which is a far more ephemeral, elusive, valuable, indefinable quality); I didn’t stop liking Woody Allen 15 years ago when we all learned that the real man wasn’t the moral paragon he played (and wrote) onscreen, and I don’t have any problem enjoying Tom Cruise or Arnold Schwarzenegger or Mel Gibson or Bruce Willis movies. (It’s true that Willis isn’t as egregious an example as those other three but he just seems like he’s generally kind of a jerk and the Kevin Smith anecdotes about directing him seem to bear this out.) I have no problem enjoying Clint Eastwood’s onscreen presence even though he supported Ross Perot and talks to furniture on TV.

But this is different. I’m in the same boat: she drives me nuts. And I haven’t seen most of her movies, which usually makes me suspend judgment, and I thought she was totally fantastic in The Dark Knight Rises (after her very first scene, I whispered to my friend, “I rescind all criticism.”) And the clip of her singing that big song seemed very good to me (and I generally don’t go in for staggeringly consequential Broadway numbers); I was fascinated by the “live singing” gimmick and actually came very close to going ahead and seeing the movie, before I came to my senses. Even Joan Rivers let me down: I thought she, if anyone, could nail it, however crassly; could put her finger on what nobody seems able to define, and I listend with bated breath when she was asked what she thought of Hathaway. But Rivers whiffed it, and just made gagging noises; even the queen of horrible putdowns (who, I remember, called Mondale and Ferraro “Fritz and tits” 29 years ago) came up empty.

But last night, I finally figured out what’s wrong with Hathaway: it comes down to one word. I gave in and followed a link to another think piece about Hathaway’s Oscar night behavior, wherein she’s quoted as responding to a question about getting married and then winning the Academy Award. And she said it was “the cherry on top of a wonderful, wonderful dish of vegan ice cream.”

And that’s it—that one word explains the whole thing. Not “a dish of ice cream,” which is a fairly straightforward conclusion to the frequently-used “cherry” metaphor: the cherry is something extra, the better thing after the (more important) good thing. (Olympic athletes talk this way; everybody understands.) And not just a “wonderful, wonderful” dish of ice cream, denoting excitement, breathlessness, winsomeness, and other good things that we like to see when people win things and are charmingly flustered. Vegan ice cream.

Because Anne Hathaway is a vegan, and she’s going to make sure that, while she’s on television, she’ll use the opportunity to proselytize for her cause. (Which I have nothing against, either in terms of form or content: I had no trouble with Marlon Brando’s stunt with Sacheen Littlefeather or, especially, Michael Moore’s challenge to George W. Bush. I like it when the Oscars are “politicized.”) But look what she did: she stuck that carefully-considered word—totally unnecessary for her simile: it’s ice cream; it tastes good and you put cherries on it no matter what kind it is—into the middle of a sentence that was supposed to be so natural and off-the-cuff that she said “wonderful” twice. She’s “gushing,” but she’s also making a point.

And that’s the whole ball game; that’s what’s wrong with her. Not only is she condescending to me and everyone listening (because she figures that this is an appropriate opportunity to advertise and to advocate her dietary preferences); she’s insulting us (mildly insulting us, admittedly) because, like somebody who “accidentally” name-drops their school or their job title or salary, she thinks we won’t notice what she’s doing; she genuinely believes that it will come across as an inadvertent nuance in her excited word-flow, and not as a carefully placed node of self-aggrandizement or advocacy.

I don’t know about you but I hate people who do that: brag or lecture in a way that I’m not supposed to notice. So that’s what’s wrong with Anne Hathaway; the subject is now closed.

Monday, March 4th, 2013

•

Politics / Writing

It’s strange to realize that you’re old enough to have seen the world change. The idea comes out of nowhere when you don’t expect it and aren’t looking for it but the frisson of recognition is always very strong—we grew up hearing our parents and grandparents talk this way and dismissing it as imposture, as willful dissociation from the present, so it’s disorienting to suddenly realize that you’re doing the same thing.

Two trains of memory collided this weekend, forcing me into the individual/historical fugue state I’m describing—but I wasn’t doing anything special; just catching up on some current events. Finding a bootleg copy of the acclaimed movie How to Survive a Plague (which just lost the 2012 Best Documentary Feature Oscar to the superb Searching For Sugar Man) and starting to watch it, I was immediately plunged back into what Gawker lovingly calls (in a pictorial feature on the passing of Ed Koch) “the gritty 1980s New York.” The Gawker selection of photographs and videos (including some bland, plotless VHS footage of subway platforms and graffiti-covered trains that had me stupefied with recognition and nostalgia) showed a vanished world, and the ensuing commentary plunged into the questions of which era was better or worse, and in what ways.

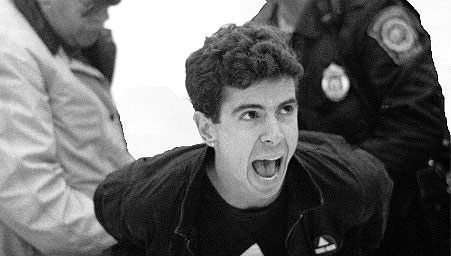

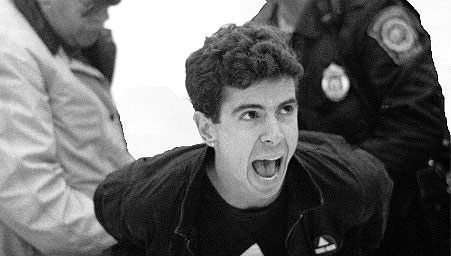

But the opening sequences of Plague are much more forceful (you see the World Trade Center immediately and the pain only escalates from there) as the 1987 “Act Up” march on City Hall unreels in riveting, ponderous amateur-video montages. Activist and editor Garance Granke-Ruta’s brilliant memoir in The Atlantic (in which the author’s direct involvement in those agonizing struggles of the second Reagan Administration—the “plague years” before AZT and other drugs were available at all—are searingly described) hadn’t prepared me for the shock of the footage itself; the screams and the police violence and the callous press conferences and news features playing out against the brightly sunlit, cigarette-smoke-drenched Manhattan that I recognize so vividly from my high school years.

My first strong memory of Reagan’s first term (aside from his shooting) was his brutal response to the PATCO air traffic controller’s strike in 1981, which Alan Greenspan has called “perhaps the most important” of Reagan’s domestic actions. My anti-labor relatives in the Midwest applauded what Reagan had done, the precedent he’d set by firing all those Federal employees (their positions have not changed) and the ensuing contentious Christmastime discussions were among the first overtly political arguments I personally involved myself in. By 1983, when Lech Walesa got his Nobel Peace Prize, I was calling myself “a liberal Democrat” (although I was years away from voting), and I understood the narrative that defined Walesa’s triumphs as a counterstrike to Reagan’s actions—a progressive victory in the struggle between labor and capital, no less.

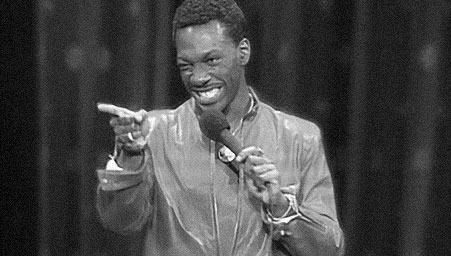

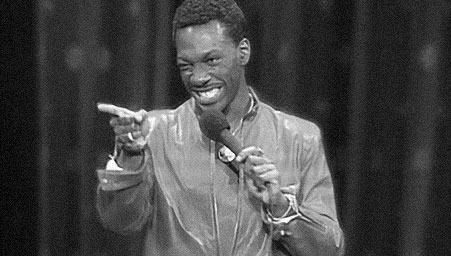

But in 1983 I was also sitting in a friend’s East 72nd Street apartment watching a VHS tape of Eddie Murphy’s concert movie Delirious, which had just come out, and which my friend’s mother had already seen and described as “just the raunchiest thing”—I remember envying that kind of parental hipness and permissiveness (she knew exactly what was on it and let us watch it anyway). The recent HBO roundtable special “Talking Funny” (with Chris Rock, Ricky Gervais, Louis C. K. and Jerry Seinfeld) had me thinking about older standup routines and (on the same day I was watching How to Survive a Plague) I ended up following some YouTube links to a complete, uploaded copy of the Murphy movie.

And it’s all about “faggots.” Murphy spends at least the first half hour of his act running through a series of riffs and bits about gays, “homos,” and “fags” that has his audience gasping for breath because they’re laughing so hard. Leaning forward peering at the miniature YouTube playback, watching Murphy (whose transvestite-arrest incident was 14 years in the future) strut and preen onstage, insisting that he “has to keep moving” so that “the faggots don’t stare at my ass” and doing mincing impressions of real and imagined homosexuals, I didn’t laugh once. I was transfixed by my memory of sitting on my friend’s carpet late at night in the summer of 1983 and smiling along with every joke, while wincing in pain and embarrassment at the same material, today.

Lech Walesa made headlines this past weekend for his universally-condemned remarks about how homosexuals in Parliament should “be behind a wall” (comments that he apparently refuses to recant). Walesa’s “legacy destroying” statement is being condemned around the world on the same weekend that the Associated Press and others are reporting that a baby born with HIV “is apparently cured.”

Thirty years after Walesa’s Nobel Prize and Eddie Murphy’s movie, the Village Voice‘s Michael Musto laments that How to Survive a Plague lost the Oscar, but points out that the structure of the voting procedure made that loss inevitable: “After all, these are the people who wouldn’t even look at Brokeback Mountain because it made them squeamish.” And yet, Ang Lee’s new, second Oscar win is being seen as “making amends” for that 2005 oversight. On my television Ed Koch is framed in blurry analog video answering hostile questions about his labeling of the Act Up marchers as “fascists” while on my computer Eddie Murphy’s audience is applauding his opening routine about the “nightmares he has about gay people” and I’m realizing that I’ve seen the world change.

Friday, March 1st, 2013

•

Politics

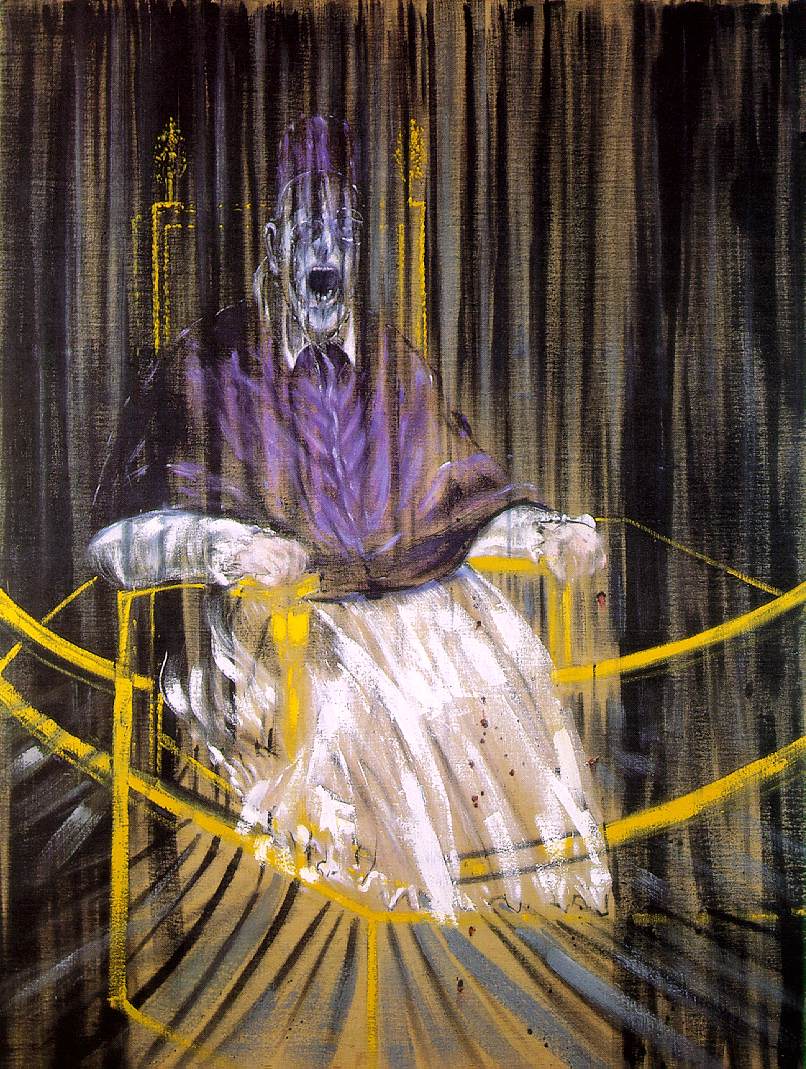

For obvious reasons I’ve been thinking about Papal authority (moral, philosophical, financial, political and spiritual) in the past few weeks. Andrew Sullivan is among the loudest voices in the chorus excoriating Pope Benedict for “destroying the moral authority of the Catholic Church” (“The only word for that is evil”). But “Doctor Science” at Obsidian Wings takes a dissenting view, basically pointing out that “the longest-running bureaucracy still in existence” is “of course” overrun with “factions and corruption.” (The specific point of contention has to do with a priest named Marcial Maciel, an accused serial child molester who was embroiled in a power struggle involving Benedict and John Paul II.) That debate, such as it is, could go on, but I was sidetracked by the Doctor’s reference to Velásquez’ 1650 Portrait of Innocent X:

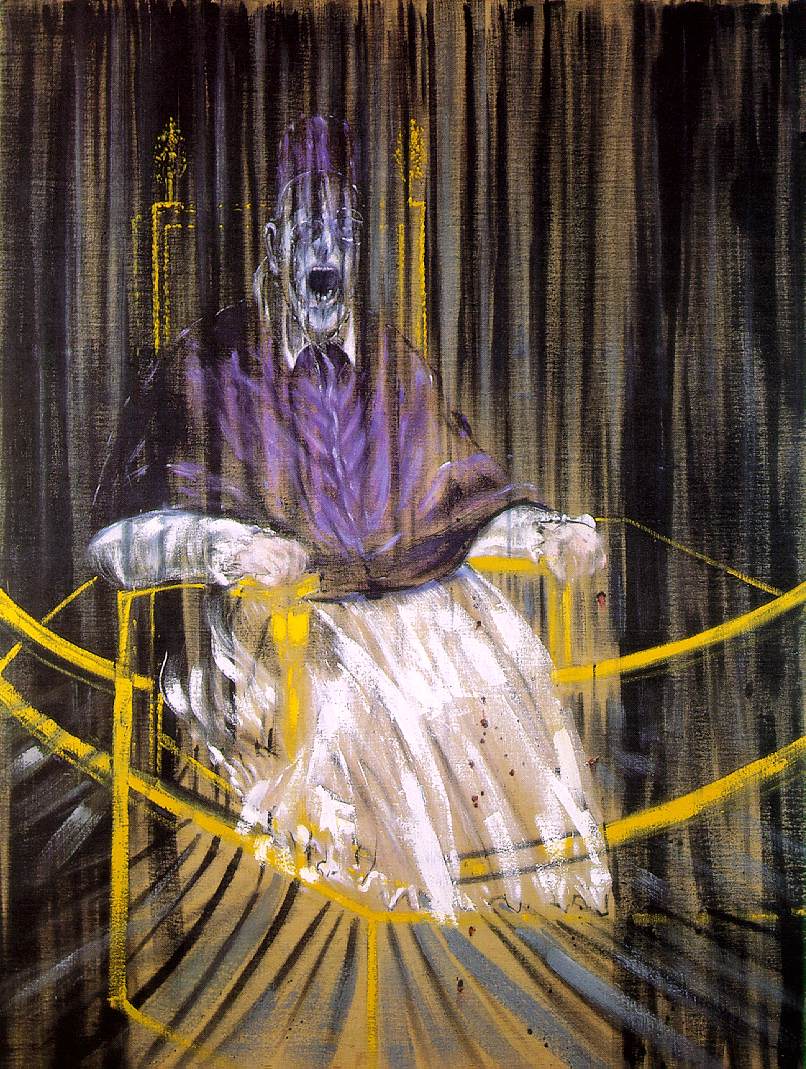

When Francis Bacon used this painting as the basis for his 1953 Study after Velásquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (the famous “screaming Pope”), he insisted that his intentions weren’t political, as he had nothing against Popes; he just needed “an excuse to use these colours, and you can’t give ordinary clothes that purple colour without getting into a sort of false fauve manner.” But judge for yourself:

I saw this painting in London at least a decade ago and I remember reading at the time that the superimposed face was from another source—and a Huffington Post article confirms that Bacon used a still from Eisenstein’s 1925 silent Battleship Potemkin (the one with the baby carriage going down the stairs, which got ripped off in The Untouchables), showing a nun screaming in the moment of being shot “while witnessing a bloodbath killing.”

Bacon (whom Margaret Thatcher called “the man who paints those dreadful pictures”—could you ask for higher praise?) died in 1992, but the savagery of his worldview and the particular lens through which he viewed both ecumenical and secular power has particular relevance today. Who knew, back then, that Sinead O’Connor was ahead of her time? Bacon didn’t throw his career away (as O’Connor did) attacking the Papacy, but the accumulated thousand cuts seem to be finally taking their toll.

ADDENDUM: I just remembered that Jack Nicholson’s Joker made his henchmen deface all the paintings in the Gotham Museum of Art, but stopped them from touching a Francis Bacon, saying, “I kind of like this one.” (It was Figure With Meat, 1954, and thank you Wikipedia.) This uncharacteristically urbane touch from Tim Burton in turn reminds me of Brad Pitt’s alleged insistence that he be allowed to smash a “New Beetle” in Fight Club (wherein his character also both directs his minions to “Destroy a piece of corporate art” and—again at Pitt’s insistence—hurls an epithet at Martha Stewart). Intermingling threads of politics and art…a phenomenon that’s certainly older than the Papacy.