Friday, October 31st, 2014

•

Design

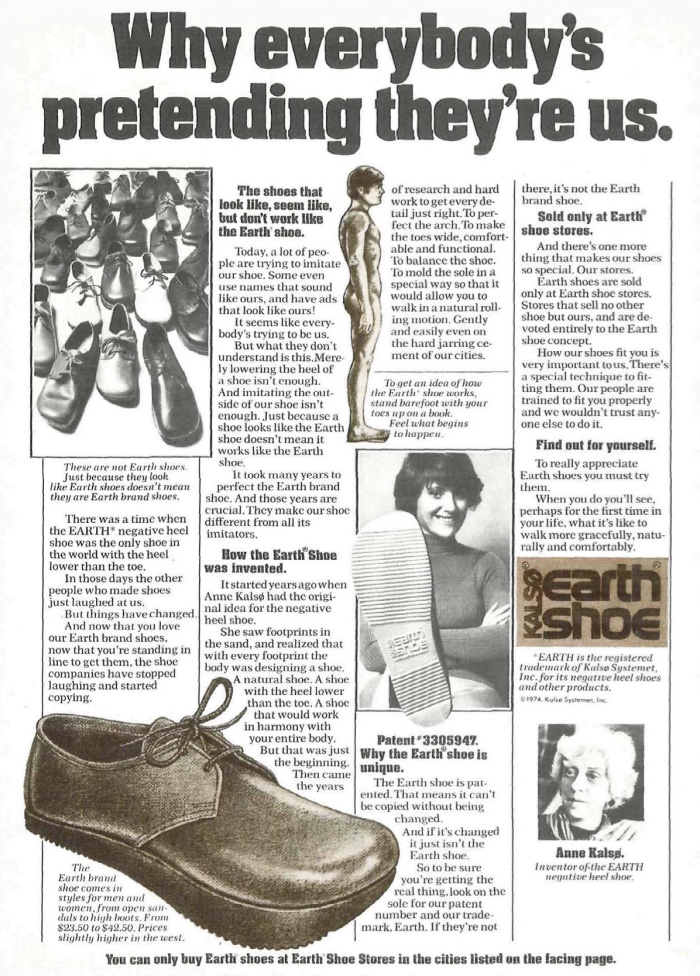

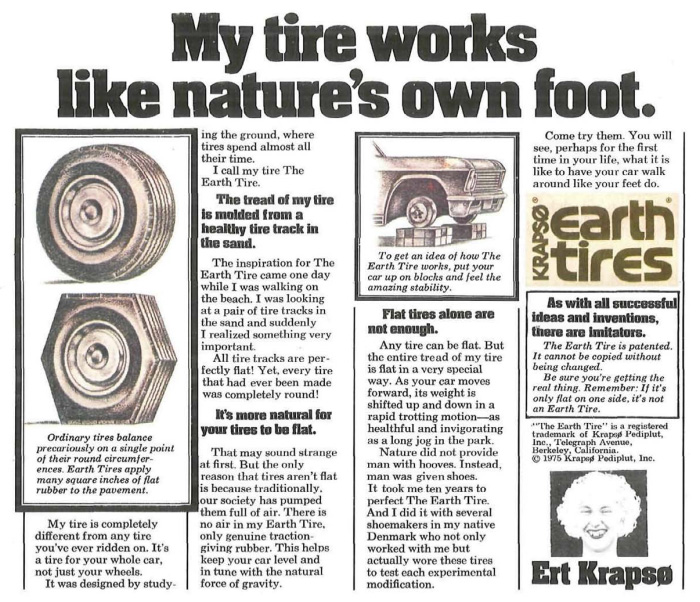

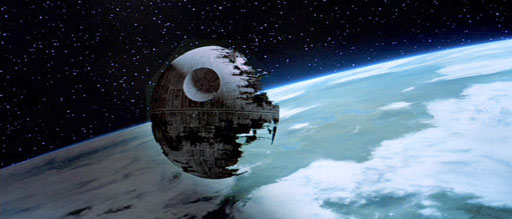

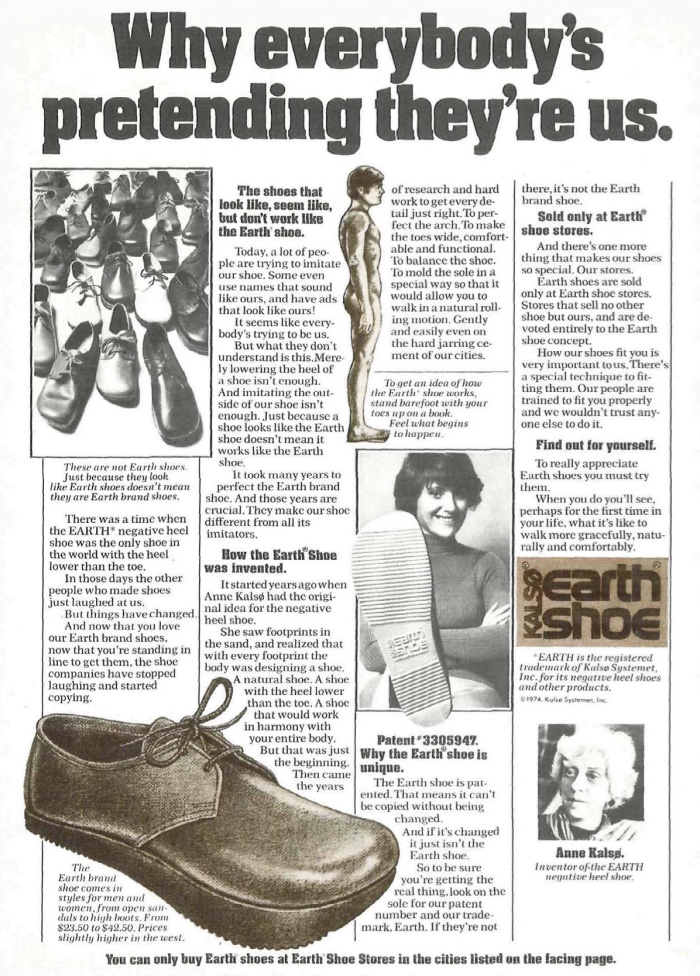

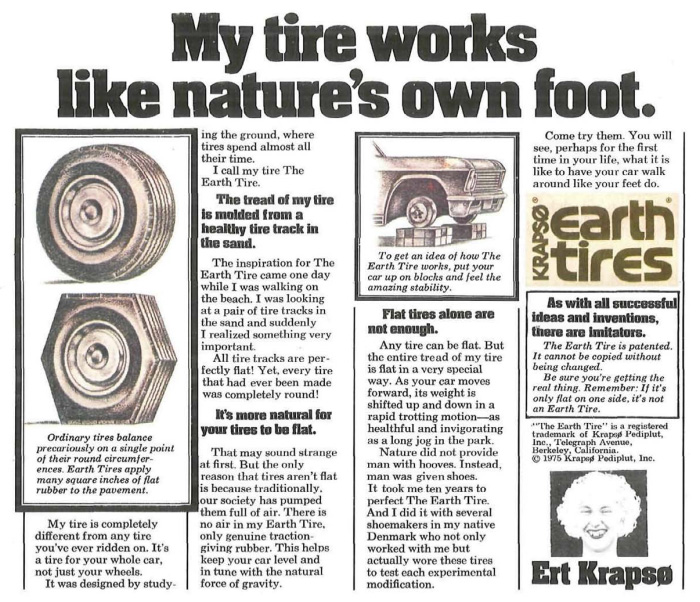

Ubiquitous early-1970s magazine ad for Earth Shoes (directly below; click for full size), and, below that, a 1974 National Lampoon parody of the same ad (for “Earth Tires”):

The “Earth Tires” ad was almost certainly written by P. J. O’Rourke (whose conservative leanings went against the grain of the rest of the masthead), author of a surrounding automobile magazine parody called Warm Rod, and visually executed by either Peter Kleinman or Michael Gross (designer of the Ghostbusters logo, among many other things), whose work at NatLamp pioneered the art of finer-grade satire that works by means of a flawless visual reproduction of the source material.

Note especially how the parody picks up the didactic tonality, the “technical” illustrations, and the overblown presentation of “Inventor Ann Kalsø” (who becomes the clearly insane “Ert Krapsø”).

Wednesday, June 18th, 2014

•

Cartoons / Writing

“Peanuts” ran from October 1950 to January 2000—nearly 50 years (“The longest continuous story ever told by a single author”). In all that time, there is not a single strip to which anyone but Charles M. Schulz applied pencil or ink—the only cartoonist ever to earn a million dollars a month was also the only one (amongst the “majors”) never to employ an assistant.

In my opinion the strip reaches its zenith exactly halfway through, in mid-1975. The artwork style and character design stops moving and changing—it’s perfected (or “calcified,” depending on how you look at it). The same is true of the jokes and narrative: essentially, it’s all been done, and he’s starting to repeat himself, moving from trope to trope—baseball field; Red Baron; Schroeder and Beethoven; summer camp; Woodstock’s idiocy; Lucy’s bitching; “Peppermint” Patty in school; etc. all circulate like a Lazy Susan—and the main psychological beats (in particular, Charlie Brown’s incredible existential characterization, which is really the lynchpin of the first two decades) get reduced increasingly to punchlines and takes.

I’m not sure what to make of this. He gets it where he wants it and then stops advancing it—but keeps doing it. The obvious counterexample is “Calvin and Hobbes,” which writer/artist Bill Watterson just ended once he knew he’d played it out (the argument would be reversed if Schulz had stopped in ’75, or if Watterson had kept going up to the present). Time doesn’t move, in the strips, like in a sitcom, and there are no aging actors and contract debates, so Schulz can just keep going forever…and it doesn’t pass to a new generation of artists and writers like Spider-Man, so there are never any “fresh takes” (or “reboots”).

Should he have stopped? There’s nothing wrong with the second half of the run (until he gets arthritis and loses his line, towards the end, which is like Redford losing his face); it’s still “Peanuts,” it’s still funny; it still sits there in the newspaper giving you a moment of Schulz zen (long after the style has become so copied that it’s no longer remotely revolutionary as it was in 1950, when there was absolutely nothing like it anywhere). John Updike kept writing those Rabbit Angstrom novels long after the first one shook up the literary world. I honestly don’t know what the “right move” is or if there is anything like a “right move.”

Friday, December 13th, 2013

•

Design / Movies

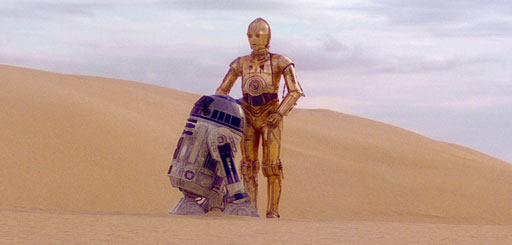

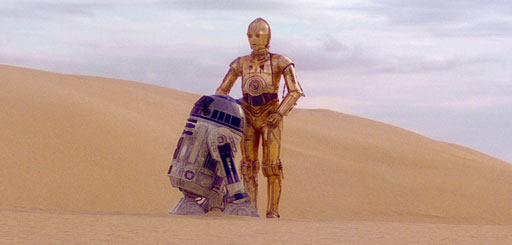

droids

Star Wars (1977)

monolith

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

metropolis

Metropolis (1927)

precognition interface

Minority Report (2002)

Enterprise

Star Trek The Motion Picture (1979)

space jockey

Alien (1979)

All-Terrain Armored Transport

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

centrifuge

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

spinner

Blade Runner (1982)

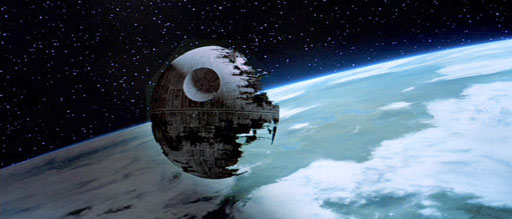

Death Star II

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Some interesting clustering of the years. Lots of fictitious machines. That may be why I’ll always prefer sci-fi design to fantasy; there’s something about the speculative precision of the imaginary technology that can evoke a far richer dreamworld than the simple escapism of Tolkienesque ornaments and runes; as with Surrealism (as opposed to pure Abstract Expressionism) the firm grounding in the observable known world provides the force of the imaginative leap. Both illustrator Ralph McQuarrie and “visual futurist” Syd Mead (who contributed major design work to Star Wars and Blade Runner respectively) had backgrounds in aerospace and automotive industrial engineering where they learned how to create elaborate, presumably human-built environments just past the boundaries of the possible. George Lucas has called McQuarrie the Star Wars MVP (he said that about John Williams, too, but Williams was post-facto—without McQuarrie’s stunning 1975 artwork—which impressed Alan Ladd Jr. and the rest of the 20th Century Fox board of directors—there never would have been a Star Wars at all).