Stephen King’s Caged Children

Thursday, October 3rd, 2019 • Writing

Readers of Stephen King’s new novel, The Institute, if they are familiar with his work, will want to find out as quickly as they can if this is one of the good ones—whether King’s familiar, crude mining tools will find a seam, how efficiently his picks and chisels will unearth the precious ores he can still pry loose from the substratum of popular fiction, and whether those retrieved riches will make the descent into those unappetizing depths worthwhile. Since King seems to have no editors, and will always be published whether he has the goods or not, there is no way to tell the duds from the winners—clumsy opening passages never get the rewrites they need, so one must wait several chapters for the engines to fully ignite. Once the volcanic, unmistakable King rocket thrust kicks in, delivering its payload of suspense, perspicacity, keen-eyed observation, mounting dread, and ambushes of unexpected emotional force, one is hopelessly trapped: nobody can propel a reader through a sleepless night like King, who somehow manages to re-ignite a buried, child-like fear of the darkness surrounding the bed that can only be assuaged by continuing to turn pages. Even when operating at full-bore, King can rarely sustain his magic act all the way through a novel: his most promising, cinema-ready big ideas tend to collapse into maddeningly inadequate denouments like those in Desperation (1996) or Under the Dome (2009), although many of his eighty-plus books—Carrie (1974); Pet Sematary (1983); the 1982 novellas “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption” and “The Body,” which was adapted as the movie Stand By Me—land like Olympic gymnasts. The new book takes longer than usual to find its way, but it proves to be one of the good ones, and it ends very well.

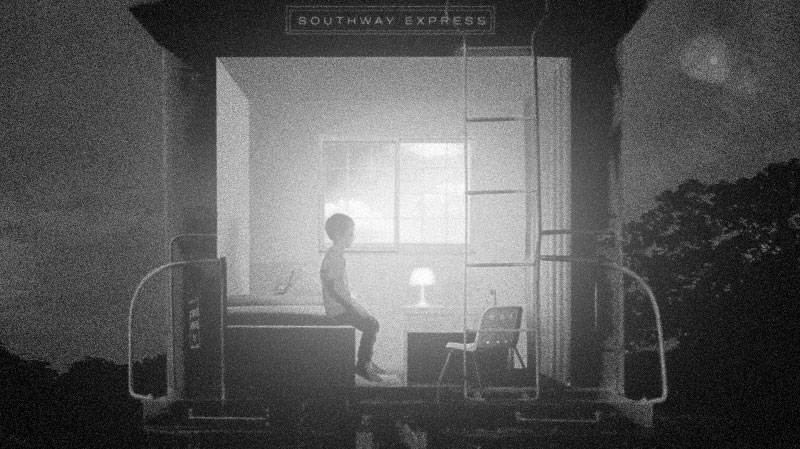

The Institute is a tall tale of children abducted away from their murdered parents, removed to a hidden government-run stronghold, and forced into a kind of slavery, and of the one prisoner, a gifted child (in the mundane, non-supernatural sense) who tries to muster the cunning and fortitude to escape. The setting is King’s usual pointedly non-cosmopolitan America, an ugly landscape of Radisson restaurants, overbooked flights, choked highways, and junk food, brought up to date with bump-stocked guns and Airpods and Rihanna songs and flash drives and WWF posters (King’s unfakable familiarity and comfort with the unvarnished consumer landscape he shares with his vast readership is as honest as Springsteen’s or Ginsberg’s). The villains are not just state-controlled captors but predatory credit-card debt-consolidators, unctuous school officials, and trigger-happy police—one of these, a Florida cop fired for a stray gunshot, eventually provides one of King’s trademark ersatz parent-child bonds with the protagonist. There is, of course, a science-fiction/fantasy armature to all of this—the prisoners are subjected to drug treatments that amplify their nascent psychic abilities, which are harnessed for assassinations—but the fabric of the storytelling is, as always, the active ingredient. King is best known for gaudy, cinema-ready scare concepts, but on the page, his mastery of structure, his dizzying control of scenes, the cavalier timing with which he throws the railway switches that propel his stories’ freight towards their destinations, remain his strongest suit, as much as his eye and voice. The Institute provides King’s expected dose of blood and terror, but along the way, there is a runaway child’s boxcar journey down the Atlantic states, with scattered views of the deepening Southern landscape, a panoramic gaze between cargo crates at the railway trestles and depots and the passing trees and stars, that has a Woody Guthrie poetry.

What is all this about? Is King describing caged migrant children, or overseas victims of outsourced black ops? (He includes pointed references to Blackwater and Halliburton, and a deep-south open-carry enthusiast calls President Trump “that big-city shit for brains.”) As in 1980’s Firestarter, which The Institute most resembles, the internal monologues of the captors and torturers smoothly rationalizing their atrocities are tuned in the direction of stock villainy but convey enough Arendt-style banality to work as blatant signifiers, recognizable to readers with even the slightest contemporary political focus. King himself, discussing the social and political meaning of fantasy in Danse Macabre, his 1981 book-length meditation on the horror genre, insists that genre fiction works best when its application remains vague and unspecific: the movie based on Jack Finney’s sci-fi thriller The Body Snatchers (1955), he writes, has been imputed to contain “all sorts of high-flown ideas” ranging across a spectrum from Anti-McCarthyism to Anti-Communism, “[b]ut in my heart, I don’t really believe that [director Don] Siegel was wearing a political hat at all when he made the movie (and you will see later that Jack Finney has never believed it, either); I believe he was simply having fun and that the undertones…just happened.” (“[S]ometimes these pressure points, these terminals of fear, are so deeply buried and yet so vital that we may tap them like artesian wells.”) The best writers of speculative fiction, King concludes in his appreciation of The Twilight Zone, echo a “Daliesque ability to create the fantasy…and then not apologize for it or explain it. It simply hangs there, fascinating and a little sickening, a mirage too real to dismiss.”

Harold Bloom, the literary critic, appalled when King received the 2003 National Book Foundation’s award for “distinguished contribution”—the same given to Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Arthur Miller—took exception in a contemptuous Boston Globe essay repeating his ongoing excoriation of American “post-literate” standards: King’s recognition was “a terrible mistake;” “another low in the shocking process of dumbing down our cultural life.” Bloom’s previous descriptions of King “as a writer of penny dreadfuls” was, he amended, “too kind…what he is is an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis.” But this misses the point: King cannot write, the way John Wayne cannot act or Bob Dylan cannot sing. His work is not literature, it’s Americana; it has the gloss and force of all unreconstructed popular art, from Norman Rockwell to Walt Disney, Frank Capra to Norman Lear, Andrew Lloyd Webber to Matt Groening, as critically problematic as all of them, and, like all of them, it aims to satisfy base appetites while humbly groping for greater meanings, occasionally making contact, retrieving the precious metals lacing through our society’s foundations. Unvarnished and crude, but vital and alive, half straw and half gold, Stephen King’s near-fifty-year span of writing continues to provide a perpetual dark reflection that America obviously wants, and probably needs.